National WWII Glider Pilots AssociationLegacy Organization of veterans National WWII Glider Pilots Association. Discover our History, Preserve our Legacy | ||

|

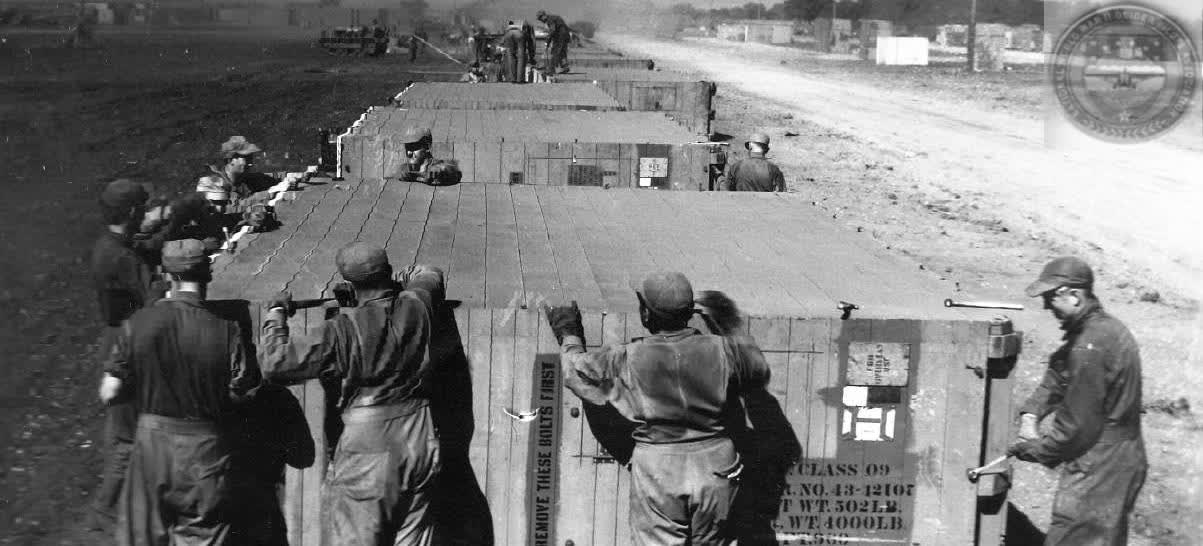

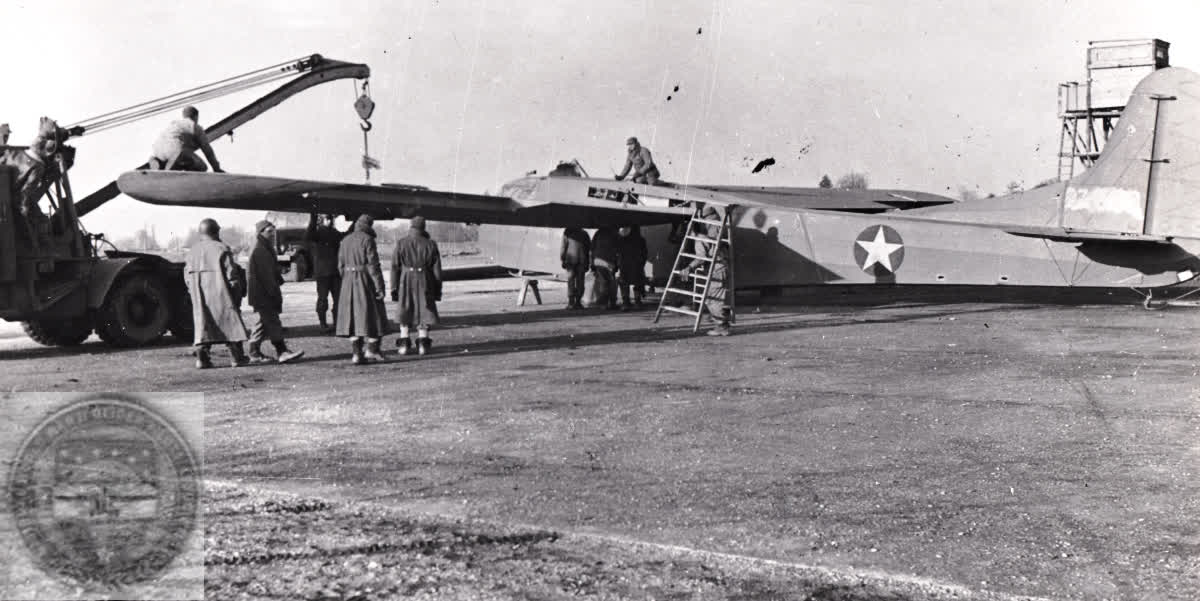

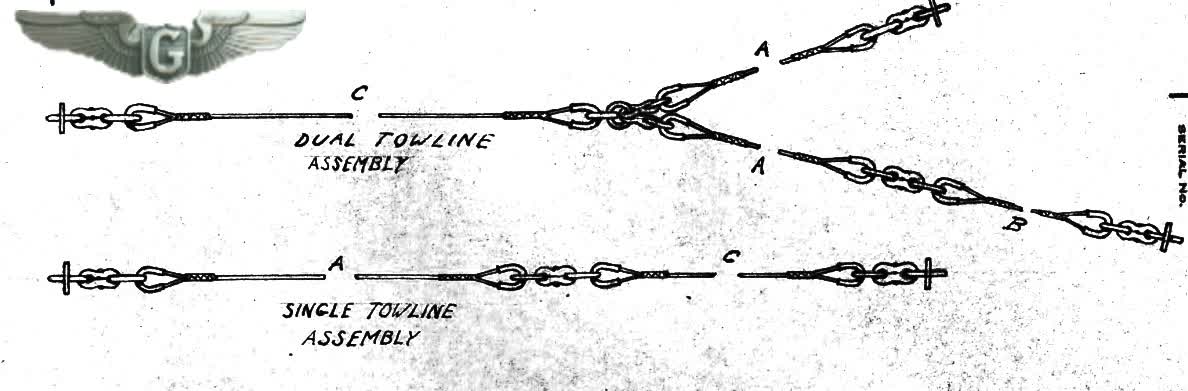

Pratt, Read & Company, Inc. of Deep River, Connecticut built 956 CG-4A gliders during 1943-45. A few of these gliders were transferred to the Royal Air Force. The British tagged these CG-4A gliders, “Hadrian”. One of the first gliders transferred was designated FR-579 and given the name Voo-Doo. Air Chief Marshall Sir Frederick Bowhill called Wing Commander Richard G. Seys into his office and informed him of the need for someone to experiment with flying freight gliders over long distances and he was willing to give Seys the assignment. Commander Seysrsquo; thought was that he “was horrified” of the idea of flying a motor-less aircraft. However, he surely was thinking his father-in-law was not trying to be rid of him in giving him this assignment! Commander Seys was sent to England to learn to fly gliders. After that training he flew to the United States to learn to fly the CG-4A glider at Stuttgart, Arkansas and Lubbock, Texas. The tug for Voo-Doo was a C-47, “Dakota” piloted by Flight Lieutenant W. S. Longhurst and Flight Lieutenant C.W. H. Thomson. The Voo-Doo co-Captain was Wing Commander Fowler M. Gobeil who later became a member of the World War II Glider Pilots Association in the United States. He sent a copy of the story of Voo-Doo to Mr. William Horn for publication in the Silent Wings Newsletter, the official newsletter of the association. Commander Seys visited the Pratt-Read factory on October 8-9, 1943. A story of the visit was printed in The Leading Edge, the Pratt-Read employee newspaper. These articles are the primary sources for the information in this article. Commander Seys, wearing the red and white cross for glider flight, the blue and white Distinguished Flying Cross and the purple ribbon for the 1936 Palestine campaign was introduced to the Pratt-Read employees by company President, James A. Gould. Commander Seys spoke of having previously obtained two Pratt, Read gliders. One glider was used for training flights. The other glider was named Voo-Doo as it “seemed to have a connection with the Indian rope trick.” The unnamed experimental sister to Voo-Doo was used for “practice.” Both gliders were early Pratt, Read production, likely late January, or early February 1943 delivery articles. The sister glider was first flown at minimum load on short hops. Gradually the load weight was increased along with the length of the flights. During “mid-winter”, this glider made a fully loaded flight from Montreal, to Newfoundland, to Labrador and returned to Montreal, setting a world, non-stop record of 880 miles. For over ocean practice flying, this glider was flown from Montreal to Nassau, Bermuda. On the southbound flight, stops were made en-route. On the return flight to Montreal, the glider was flown from Nassau to Richmond, Virginia setting a new non-stop flight record of 1,187 miles in eight hours and fifty minutes at the average speed of 134.4 miles per hour. The Voo-Doo trans-ocean flight was divided into four legs. It began at Montreal on June 23, 1943 around 1200 hours and ended at Prestwick, Scotland at 1311 hours on July 1, 1943. Before the flight began and despite clear sunny weather, odds makers at the aerodrome in Montreal were giving 7 to 1 odds against a successful crossing. The Dakota tug was equipped with additional fuel tanks making the full fuel load approximately 1,800 gallons, producing a flight range of approximately 2,450 miles. Beginning with this full fuel load, the Dakota towed the Hadrian at near 120 miles per hour for the first four and a half hours. As the fuel load decreased, the tug was able to increase the tow speed to around 140 miles per hour for the duration of that leg of the flight. Voo-Doo carried just over 3,000 pounds of assorted cargo consisting of blood plasma for Russia, equipment for the Free French, B-24 bomber parts, Ford truck parts and a lot of fragile radio parts. There were no bananas in England and there would none for the duration of the war, so Commander Seys carried a bunch of bananas to his family in England. As the tug-glider train approached the Atlantic, clouds estimated to be greater than 25,000 feet began appearing. The tug and glider, without oxygen, could make only about 13,500 feet altitude, so they flew under the cloud formation. The ride became extremely rough as the glider bounced from side to side and up and down behind the tug by as much as 100 feet. One minute the air speed was 160 mph and the next it was 95 mph. The load began to shift slightly while the tow line was stretched tight or “hanging like a limp string.” The temperature dropped below freezing, frost formed on the inside of the glider and ice began to form on the wings. They flew around some black rain storms and through others, flying by the meager instruments in the glider. After three hours of this strenuous flying, they arrived over Goose Bay, Labrador. The glider cut loose at 1,000 feet and landed at the aerodrome. This leg was 850 miles, flown in 6 hours and 47 minutes for an average speed of 125.3 miles per hour. Laying over for more favorable weather, the second leg was begun on June 27. This flight was mostly above large cloud formations giving the glider pilots a bit of relief as though the ocean was not really there. Five hours into the flight B-26 bombers on their way to England flew past so quickly the glider crew felt as though they were going backward. The runway at Greenland was steel mat (Marston strip) surrounded on all sides by snow-capped mountains. The tug and glider flew up the fjord toward the airstrip and Voo-Doo cut loose at 7,000 feet and glided over the huge icebergs making a perfect landing. Although this flight had been uneventful compared with the first leg, the tow line was found to have one of the three strands at each end almost worn through! The tow line was re-spliced and the aircraft were made ready for the next leg. This Labrador to Greenland leg was 785 miles, flown in 6 hours and 13 minutes for an average speed of 126.3 miles per hour. June 30, after a two-day layover, the weather cleared a bit and the two aircraft took off on leg three heading for Iceland. This leg was the longest air mileage of the trip. The take off from Greenland was a bit scary because the runway ended at the bay that was full of icebergs. A normal powered aircraft takeoff was full power with lift off a few feet from the water’s edge, and a hard climb to 12,000 feet to clear the mountains. The Dakota with the Hadrian on tow would require every inch of runway and possibly more. Because they could not possibly follow the usual powered climb over the ice fields surrounding the mountains, the Dakota and Hadrian were forced to take off low and head down the fjord, gradually gaining altitude as they approached the open sea. The Hadrian lifted normally but the Dakota, to gain speed, was held on the runway until the last second, leaving the ground just two feet from the water! They encountered a few air current bumps flying down the fjords but 30 minutes after take off they reached 5,000 feet. The direct flight from Greenland to Iceland is approximately 810 miles flying over the 12,000 foot tall Greenland ice cap. Because the train could not fly the altitude required to clear the 12,000 foot ice cap, they had to circle Cape Farewell adding 200 miles to the flight. As the train passed Cape Farewell, a solid cloud bank enveloped them for more than an hour. The air was turbulent, the glider pilots could see only approximately 30 feet of the tow line and it began to snow INSIDE the glider! This internal snowstorm subsided and it began to snow outside. The tug had begun a slow climb to get out of this rain and snow weather. The glider pilots were exhausted and wondering if they could carry on when suddenly, after a succession of violent bumps, they broke out of the top of the cloud at 11,500 feet and guided the glider back into proper position behind the tug while flying between layers of clouds above and below. This proved that it was “possible to take off with a fully loaded glider and climb safely through thousands of feet of cloud to reach a suitable cruising altitude.’ Approximately three hours from Reykjavik, Iceland, the tug “waggled its wings.’This was a signal to turn on the walkie-talkie that was left off to conserve battery power. The tug pilots wanted to tell the glider pilots the Reykjavik weather was unlimited ceiling and visibility. Just under an hour out, the train was met by three USAAF fighter planes. They had been requested from Greenland because the area was reachable by long-range German planes flying from Norway. Although USAAF fighters had shot down more than a dozen of them, German planes frequently appeared over Reykjavik. The glider cut loose over the English aerodrome at 5,000 feet and made a perfect landing. Because many small homes surrounded the airfield, the tug had to drop the tow line on the hard surface runway. This damaged the aluminum thimbles on each end of the line causing the crews to wait for the thimbles to be replaced and the eyes spliced. This Greenland to Iceland leg was 1,000 miles flown in 7 hours and 20 minutes for an average of 136.4 miles per hour. Leg 4 began July 1 after the Dakota and the glider had been serviced overnight. This leg was over the Russian convoy route frequented by German bombers. USAAF fighter escort was requested to a point halfway between Iceland and the British Isles. Royal Air Force fighter escort was requested from that halfway point to the British coast. Unfortunately, neither of these escorts appeared. Fortunately, the German bombers did not show either. Five hours from Iceland, the pilots got first glimpse of British soil, a large rock in the sea near the Hebrides. Nearing the mainland in a heavy haze, they flew into an unexpected balloon barrage. The tug pilots had not been advised of this barrage during their briefing at Reykjavik and some smart flying was accomplished to keep from flying into the balloons which were deployed at varying heights. Perhaps another first was achieved at this point. While evading the balloons, at one point, the Dakota flew over the Hadrian, each flying in the opposite direction! At 1255 hours, Voo-Doo and the tug were circling the Prestwick Aerodrome waiting for a photography plane to film them as had been done when they left Montreal. Before the photographers arrived, the broken cloud cover closed in. Being cautious and wanting to get on the ground before the cloud cover thickened, the glider cut loose at 5,500 feet. The pilots dove through the solid cloud cover breaking into the clear just below 3,200 feet, sighting the airport a few miles away to their port side. The touch-down was a normal landing at 1311 hours delivering their varied cargo safely. This leg was 865 miles flown in 7 hours and 43 minutes for an average of 112.1 miles per hour. After the flight, the flight personnel met for debriefing and decided trans-Atlantic glider service was not feasible using equipment currently available. They cited six reasons why the service could not be feasible.

After this flight Voo-Doo was scheduled for placement in the British National Museum. A ferry crew flew the glider from Prestwick, Scotland to a more southern aerodrome in England. On landing, the glider crashed. The glider was demolished. It was an irreparable pile of steel tubing, fabric and plywood. Luckily, the pilots were not hurt in the crash and both walked away from the heap of steel tubing, fabric and plywood. A piece of the tow line mounted on a display board, signed by those involved in the flight was sent to the Pratt, Read Company. This purportedly resides somewhere in the Smithsonian. A similar board resides at the Museum of Army Flying at Middle Wallop, England. The entire journey was 3,500 miles with flight time of 28 hours and 3 minutes, averaging 124.8 miles per hour. Commander Seys’ bananas were “frostbitten’ and did not make it to England. Not soon enough for WWII, but by 1946, features correcting the above suggestions were implemented in the CG-13A and CG-15A gliders. Although other stories have been written about other glider tows and called them the Longest Tow, this flight was the true and real Longest Tow. ======================================== Information for this article was collected during the author’s personal visits to the Deep River Historical Society, Deep River, CT and to Museum of Army

Flying, Middle Wallop England and during the author’s research for Silent Ones WWII Invasion Glider Test and Experiment Clinton County Army Air Field Wilmington Ohio.

In 2020 Dr. Mark Felton is a well-known British historian, created this video. Note: Voo-Doo was a CG-4A not a CG-4 as indicated on the film. The CG-4 was a test glider.

|

CG-4A WWII CARGO GLIDER GENERAL SPECIFICATION - CG-4A

Wing Span -- 83', 8" Length (Overall) -- 48', 3-3/4" Height -- 12', 7-7/16" Weight, design -- 3,750 lbs Gross Weight, design -- 7,500 lbs Wing Chord -- 10', 6" Specs for covering the CG-4A call for: Flightex Intermediate airplane fabric manufactured by Suncook Mills, or an equivalent light airplane cotton fabric. More Specifications

CG-4A WAS FLIMSY? COMMUNICATION SYSTEM CG-4A Loads CG-4A Load Facts CG-4A Cockpit CG-4A Instrument Panel  STORIES:

|

The HORSA GLIDER |

GLIDER PICKUP/Snatch Snatching a Glider RECLEMATION American Glider Pilots Captured by British A/B by William SIMONSEN Double Snatch by Charles Day First Glider Snatched from Normandy by Gerald BERRY REMAGEN Glider Retrieval by Jungle Moonlight: Burma, 1944 by Leon SPENCER Charles DAY Keith H. THOMS NWWIIGPA Deputy Wing Commander

Eastern United States Military Snatch Pickup Summary

Glider Pilot Check List

Glider Ground Crew Check List

|

OUR TOW SHIPS |