With Normandy, Southern France and Holland combat mission’s history behind them and what seemed to be a lull in the action, the 88th Troop Carrier Squadron resumed its routine training program during the second week of December. Most of the work included glider tows for the purpose of indoctrinating the men of the 17th Airborne Division.

On December 12, 1944 the 88th squadron, stationed at Greenham Common, RAF Station #485, was engaged in giving a local orientation ride to members of the 17th Airborne. It was a clear day for flying. Horsa glider LJ 132 was flying number two position in a formation of the four gliders on tow. It had taken off, made a complete circuit of the air field, and was flying over the field in the direction of takeoff, at an altitude of approximately 600 feet above the ground. It was observed from men on the ground and glider pilots in following echelons that the glider was experiencing some difficulty. The glider had cut loose and it was evident that bits of the tail assembly were disintegrating. It appeared that the left elevator tore loose from the horizontal stabilizer. Unable to control his glider, the pilot, 2nd Lt. Alfred C. Buckner, pulled the release and cut loose from the tow plane. Several witnesses reported what they saw:

1st Lt. James E Maxwell, O-680051, AC was on the ground when he reported:

...at about 1600, I was standing in the 88th TC Sq. Operations Office facing towards the west, when I happened to glance out the window to see some black objects coming from a Horsa glider.

At first I thought that it was refuse thrown from the tow ship of the glider, but in the next instance I realized that the glider was loose from the tow ship and that more pieces were falling from it. I watched it start a shallow dive at first and then it went into a step dive out of my sight

I made an exclamation about a glider falling, which was heard by the office personnel. Some of the officer personnel and I started towards the spot that I thought the glider had crashed. By the time we found it, the proper authorities had already been notified.

The pilot of the tow plane, 1st Lt. O. B. Phillips stated:

I was pilot of C-47A aircraft, serial number 42-24180, towing Horsa glider serial number LJ 132, at 1545 hours, 12 December, 1944. We had taken off on runway 29, made a complete circuit of the field, and were in the process of turning left over the same runway, at an altitude of approximately 700 feet, when the glider cut loose. Airspeed was 100- 110 miles per hour. There was no means of communication with the pilot, and I could feel no unusual change in his attitude of flight immediately before he cut loose.

Pilot Lt. A. A. Best who was flying over the airfield at the time reported:

I was pilot of L4-H aircraft #43-30035 and was flying over the airfield at 1545 hours…I observed the glider Horsa LJ-132 shortly after it had cut loose from the tow-plane and noticed pieces flying from the glider. The glider immediately assumed a nose-down attitude of flight, and headed straight for the ground at an angle of approximately 45 degrees.

Lt John J. Beaman was in the 4-plane formation towing a Horsa glider and was directly behind Horsa glider LJ 132. He stated:

Altitude of the flight was between three and four hundred feet and the airspeed was between 105 and 110 miles per hour.

I saw the left elevator of the Horsa in front break away. This was followed immediately by the right elevator at which time the glider pilot cut himself loose.

The nose of the glider at the time of the cut-off started descending and the glider continued toward the ground with about sixty decree negative angle of attack. It continued toward the ground at the same angle and never did flare for the landing. It crashed into the ground hitting a pine tree just before the impact with the ground. This pine tree sheared off the right wing of the glider. Upon impact with the ground the glider telescoped. As the glider hit it began to disintegrate at which time I had flown out of the line of vision.

The co-pilots, 2nd Lt. A. N. Cooper for Phillips and 1st Lt. Michael Byelene for Beaman, certified the pilots’ statements.

|

|

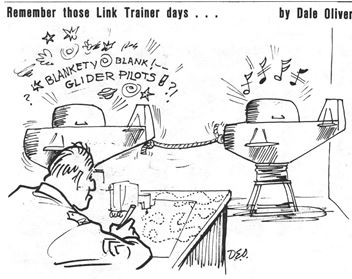

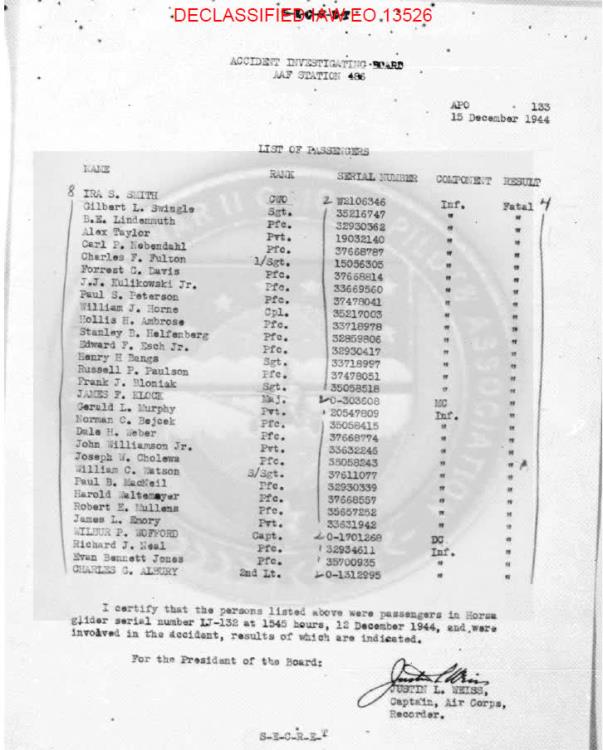

When the glider hit head long into the ground it was smashed to bits. Medical aid reached the scene approximately fifteen minutes later, at which time all of the 31 passengers and two crew members were dead. It is assumed that all were killed immediately upon impact.

As the statements verified the immediate cause of the accident was loss of left elevator in flight, followed by loss of right elevator. Loss of control surfaces was due to excessive interior moisture, which deteriorated wood and weakened glue holding in place left outboard elevator hinge rib. When this rib was torn loose from the horizontal stabilizer, the left inboard hinge rib also was torn from the stabilizer. The right elevator gave way immediately thereafter, leaving the pilot no vertical control. Exhibits E and F show the tail section after the crash, minus the elevators, which were found several hundred yards before the spot where the glider struck the ground.

he Horsa glider is a British made glider that was used by the Americans during the Normandy operation due to the shortage of the American WACO CG-4A glider. With the experience of Normandy the American pilots did not feel the Horsa was ideal for combat and did not like landing them in small landing zones. They also needed breaks to decelerate. Unfortunately, these hydraulic breaks would get damaged by flak and small arms fire during landing and many of the Horsas ended up plowing into tall tree hedges at 80 to 100mph causing considerable damage to troops and equipment. After Normandy the IX Troop Carrier Command ordered the Americans to only use the CG-4A glider for combat. I can only speculate that the reason they used the Horsas for this orientation was that they could get double the amount of men in a Horsa glider (31 troops) than they could in a CG-4A (13 troops). And the CG-4As were probably being used for glider training as they took advantage of every nice day in England.

Immediately after the crash the 12 Horsas of the 88th Squadron were grounded.1

At 2330 hours a teletype from Greenham Common was sent to the IX Troop Carrier Command as well as the commanding officer of the 53rd wing that all Horsa gliders on all American airfields be grounded and thoroughly inspected.

In the Horsa glider there are drainage holes to provide disposal of excessive moisture but it was determined that not all the models allowed “adequate facilities for inspection of the horizontal stabilizers on the Horsa glider.” The CG-4A glider has a removable opening that allows for inspection of the horizontal stabilizer and it was recommended that the Horsas have inspection plates installed.

In the accident report for LJ 132, paragraph number three under RECOMMENDATIONS TO PREVENT RECURRENCE OF THIS ACCIDENT was the most descriptive and telling of the report.

A thorough inspection of the other portions of the horizontal stabilizer and elevators of this glider reveals that there is damp rot and deterioration in many places. This condition is apparent only when the plywood skin had been cut away and the outward appearance is excellent. It is due largely to the damp climate which the glider has been continually exposed. However, it is felt that the use of glue which is not waterproof has accelerated this decay. If Horsa gliders are to continue in service, it is the recommendation of this board that all defective gliders be returned to overhaul facilities. All glued joints should be refinished with waterproof glue, the quality of the wood used in construction should be accurately determined, and additional inspection openings should be provided where necessary.

THIS ACCIDENT was the most descriptive and telling of the report.

These casualties marked the first loss this squadron has sustained in all its training programs in the eighteen months of activation. The 88th history reported that funeral services for the two glider pilots, 2nd Lt. Harry Croke and 2nd Lt. Alfred Buckner, were held at the United States burial grounds at Cambridge, December 15th. I the history of the 17th airborne would show that all the airborne troopers who died had their funeral also held that day.

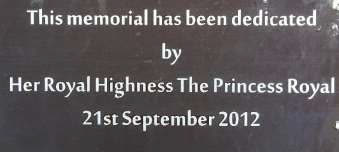

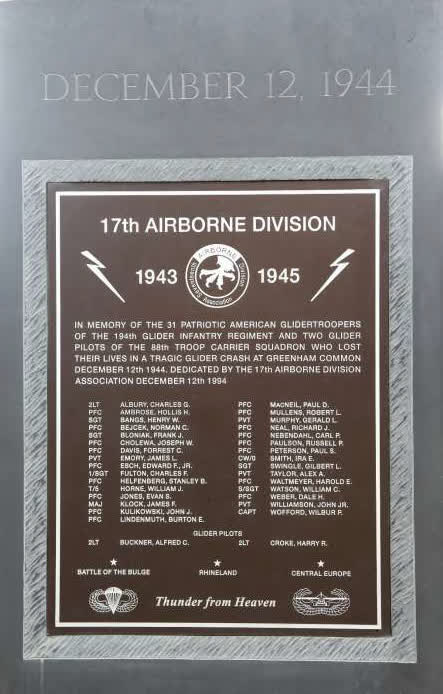

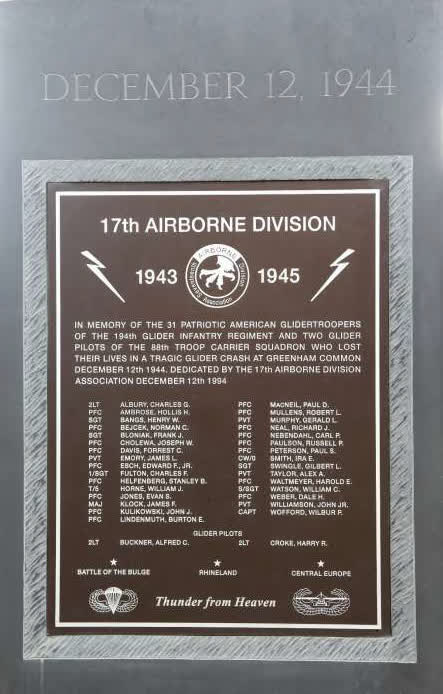

| The men who parished in this tragic accident have never been forgotten. On the 21st of September 2012 the men were honored with a memorial dedicated by Princess Anne in memory of all 33 deaths. This memorial is located on the grounds of the Greenham Common Industrial Park. The memorial also included a crash where two B-17 had a mid-air collision right over the airfield. It was not a good month for the 438th Troop

Carrier Group. |

________________________________

1Related document: 2nd Lt. James Colimore report regarding a Horsa emergency landing during the same 17th Airborne Orientation

Sources:

- Air Force Historical Research Agency, Maxwell AFB88th Troop Carrier Squadron Historical Diary, December 1944.

- Air Force Historical Research Agency, Maxwell AFBReport of aircraft incident 45-12-12-521

- National WWII Glider Pilots Association Database

- Pay, D. R. Thunder from Heaven: Story of the 17th Airborne Division, 1943-1945

|