National WWII Glider Pilots AssociationLegacy Organization of veterans National WWII Glider Pilots Association. Discover our History, Preserve our Legacy | ||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

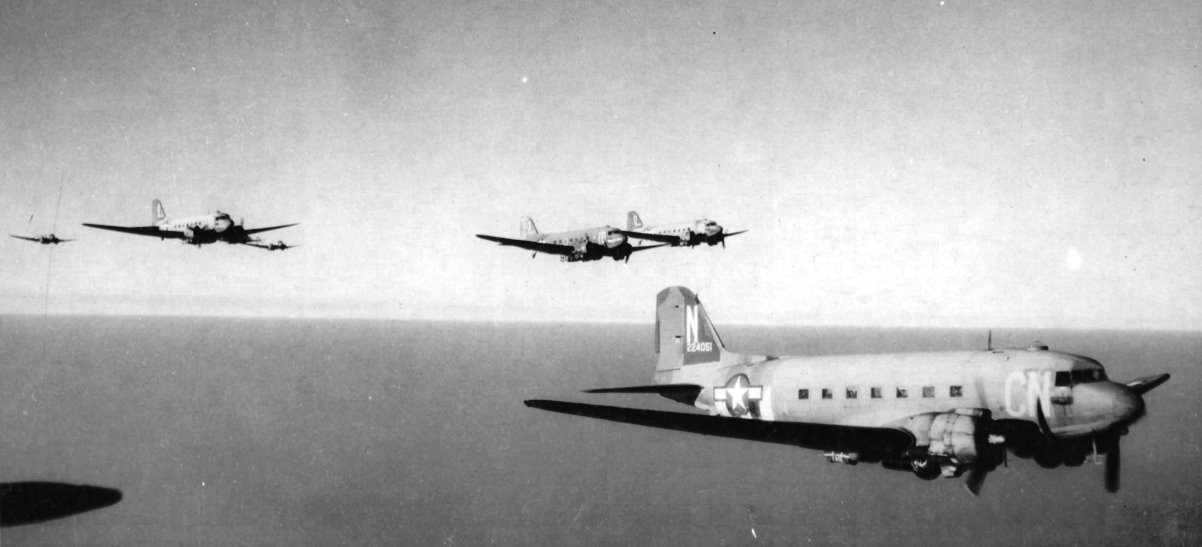

26 December 1944 [22 Glider Pilots]According to the December 1944 50th Wing Historical report: This was a big day for the 440th Troop Carrier Group, as Wing Operatons Oder No. 361 called for a tactical resupply mission, under No. 1098, with one aircraft and glider and still another, under No. 1099, using 10 planes and 10 CG-4As.Single Glider With Medics and Medical SuppliesWith the capture of the “majority of the 326th Airborne Medical Company” on the 19th of December, surgeons were desperately needed at Bastogne. The 50th Wing had planned a single glider mission carrying medical staff (five medical officers and four medics of the Third Army) and their supplies for 25 December. The weather delayed that mission until the 26th. The 440th, 96th squadron, was chosen for this mission. The C-47 took off from A-50 Orléans at 0900 towing a CG-4A glider piloted by 2nd Lt Charlton W. Corwin, Jr and F/O Benjamin F. Constantino. Their destination was Bastogne via A-82, Verdun, France, where they were to pick up their medical staff and supplies. They took off from A-82 at 1436 and they had a P-47 fighter escort for the sixty-seven mile flight which would take just over thirty minutes, the last seven minutes of which would be over German armored units. The P-47s stayed with the glider and it’s tug the entire distance. The tug flew the glider in at 300 feet but the low altitude did not allow good visibility of land marks for the LZ. There was confusion as to the correct LZ area and the glider ended up landing at 1730 1000 yard inside the German line. They were rescued by B Company 1st BN , 101st A/B and the personnel were immediately transported to the division hospital. This mission was deemed very successful with the lone glider landing without damage to crew, passengers, or cargo. This set the flight profile for the next missions. There was an interesting note in Rex Shama’s book Pulse and Repulse; Lt. Mauck was watching the glider from the Astrodome to see if it would land safely. As Lt. Ottoman banked left to make the return flight, Lt. Mauck noticed the resupply mission of the C-47s dispatched for Operation Kangaroo coming from a southern route and noted they were covered with black puffs of flak. Ten Glider Mission:On the 25th of December the IX Troop Carrier Command decided 10 gliders from the 50th Wing would make an “Air Cargo,

Resupply” mission.

In the early morning on the 26th the 440th Troop Carrier Group received orders regarding their cargo—3000 gallons of 80 octane gasoline. Each glider

would carry 300 gallons of gasoline in five gallon jerrycans¹ lashed together and secured to the floor behind the pilots!

[Gasoline and 5 gallon cans, A primer]

Take off time was 1510, five hours later than the orders which had specified 1000. This lateness was due to briefing, loading and positioning the tugs and gliders onto the airfield. However, this late take-off allowed the gliders to land after sunset and before the moon was up. This action probably accounted for all gliders making it to or near the LZ at 1710. Gliders were damaged by flak and small arms fire but miraculously no incendiary rounds struck the gliders and all gliders, with the exception of a few bullet holes in some of the jerrycans, landed without casualty. All ten tugs made it back to the airfield at Orléans all be it with numerous bullet and flak holes. One C-47 took seventy hits. This mission was 100% successful but it was advised in the intelligence report that subsequent missions should stay to the right of this route; away from the areas of Morhet and Sibret. 50 Glider Resupply -- Operation Repulse27 December 1944 [50 Glider Pilots, no coplilots] Mission #1117The 439th and 440th Troop Carrier Groups prepared a final fifty glider serial resupply mission on 26 December to the 101st at Bastogne. This mission was delayed one day due to weather. Lack of current intelligence was a concern to the Commanding Officer, Col. Charles H. Young, of the 439th. When Col. Young learned that the pilots of the ten glider gasoline resupply mission were returning to Orléans at 1900 he made the decision to travel that night of the 26th by car to Orléans to get as much intelligence on the situation as possible. When the 439th received the orders for the 50 glider resupply they began the task of assigning crews. The logistics of locating and transferring one hundred glider pilots was quickly proving to be more difficult than anticipated. This shortage of available glider pilots lead to the decision by those in command to fly without copilots. Though never officially recorded, due to the precariousness of the situation in Bastogne, the mission planners were not optimistic that these glider pilots would be able to return for future missions. So, the reason for no copilots could have been to minimize the potential loss of pilots. Fifty tow planes and gliders were marshaled on the A-39 airfield. The 439th furnished thirty seven aircraft and fifty gliders. The 440th dispatched 15 aircrafts from their airfield at A-50, Orléans/Bricy, Fr., to A-39 Châteaudun, Fr. The 95th dispatched eight, 96th dispatched seven but two were not needed and returned to A-50. The 440th was marshaled at the end of the airfield behind the 439th, chalk numbers 38 through 45 were from the 95th Troop Carrier Squadron and chalk numbers 46 through 50 were from the 96th Troop Carrier Squadron. A few minutes before take-off the 50th Wing HQ relayed a different flight route with no explanation as to the reason for the change. Young was concerned that a delay of the mission to re-brief the crews would be detrimental to the 101st as they were desperately low on ammunition. The main cargo in the gliders was ammunition. Col. Young made the decision to go as planned rather than delay the mission by one more day. Col. Young may not have known this at the time, but the armament brought in by Patton’s 4th Armored Division was also in need of ammunition. Take-off time was 1025. 50 Glider Resupply --Casualties Caption on back: A Douglas C-47 that crashed in field near Bastogne, Belgium [This was Capt. Ernest Turner's Aircraft, Ain’t Miss-behavin, from the 94th TCS Chalk #36. .50-caliber machine-gun fire took out the left engine, Turner did not release his glider but kept on towards the LZ. When the right engine was hit Turner hit the tow released ordered everyone out and belly landed the plane in an open field. They were rescued by the 321st Glider Field Artillery Battalion headquarters. Turner's glider, piloted by F/O Albert Sehman Barton, landed almost two mile west of Bastogne just south of the Bastogne-Flamierge road and less than a mile inside the 101st Division perimeter. Six men from the 101st came out to greet the pilot and thank them for the much needed 155mm ammunition and the the most precious cargo consisting of four surgeons. Throughout Barton's life he attributed his ability to get to friendly territory to Turner's decision not to release when he was first hit, he appreciated those ten seconds. (

Shama 254)

“ Two hundred eighteen crew members flew in the fifty C-47 tow planes on the 27 December glider mission. Thirty-nine did not return, seventeen were killed in action (KIA), one died of wounds (DOW), and twenty-one were taken prisoners; an eighteen percent loss. Of those who returned from mission, twelve were wounded or injured. fourteen C-47s—28 percent—were shot down. ¹ The rectangular footprint of one of these cans allowed exactly 60 cans to fit on the floor of a CG-4A, front to back and side to side. --C. Day

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

← BACK

CONTINUE →

References | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

SERIALS

50 GLIDERS SERIAL

GLIDER PILOT NARRATIVES

The SITUATION

23-24 Dec. Bundles From The Sky

C-47 Battle_Damage

26-27 Dec. Gliders

27 Dec. The Final Drop

the Murder of Lt. Epstein

Harold Russell’s Escape

Headquarters, 440th Report 1944

SERIALS

AMERICAN GLIDER PILOTS INVOLVED IN THE ARDENNES (BASTOGNE PULSE AND REPULSE) OP.

Courtesy National Archives /

NWWIIGPA Collection<

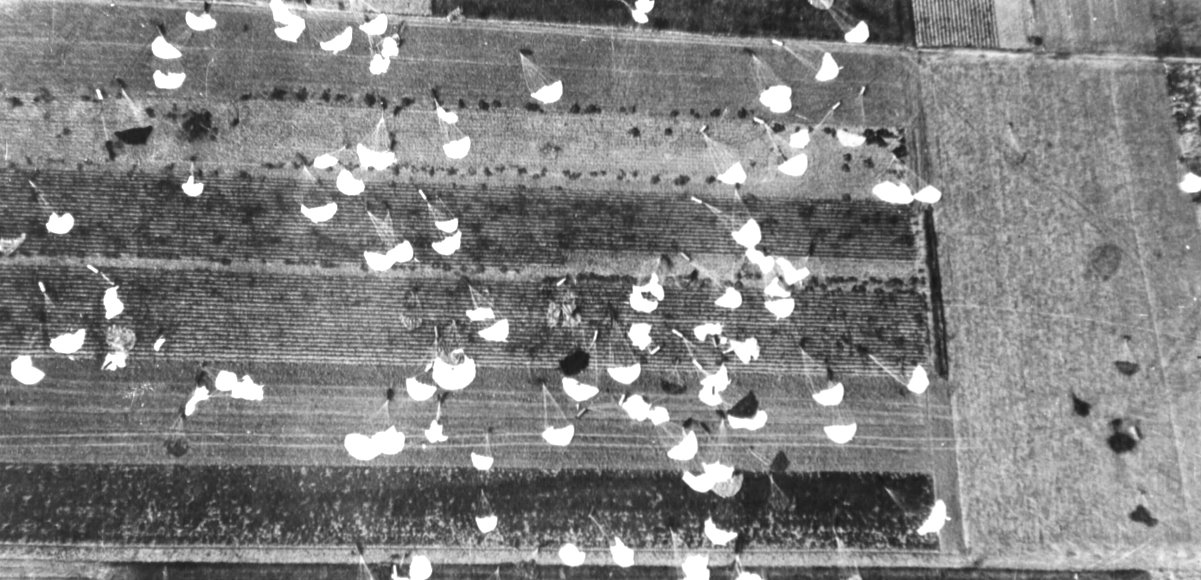

Aerial Photo of gliders in the snow covered fields

Photos of some of the men

from the 10 Glider mission:

This is Chalk #3 flown by 2nd Lt. Morris Albert Gans, Chuck Berry’s glider #4 was next in line for take off.

Photos of some of the men

from the 50 Glider mission:

F/O Claude A. “Chuck”