National WWII Glider Pilots AssociationLegacy Organization of veterans National WWII Glider Pilots Association. Discover our History, Preserve our Legacy | ||

A History of its Development and Use

The technique of retrieving an object from the ground by an aircraft on the fly was not new when the US Army Air Force (USAAF) began experimenting with such a system in 1941. Its objective was to find a means of retrieving big military troop/cargo gliders from areas inaccessible to powered aircraft. The US Marines had used a rudimentary aerial pickup system as early as 1927. It was simple but functional. A wire with a weight on the end was trailed behind a surplus World War 1 de Haviland single-engine DH4 biplane. As the aircraft flew over the ground station the trailing wire engaged a rope loop suspended between two poles to which was attached a leather pouch containing dispatches. Twelve years later, in 1939, Richard C. duPont, a descendant of E. I. duPont, founder of the giant DuPont Chemical Company, teamed with Dr. Lytle S. Adams, a dentist/inventor born in Paint Lick, Kentucky, to refine an aerial retrieval system designed by the latter. Dr. Adams, a direct lineal descendant of John Adams and John Quincy Adams, actually designed the system. Beginning work in 1929 Adams made many improvements to the system and by 1935 it had become the looped line on two poles with a hook dangling from the airplane to snag the line. Adams chartered All American Aviation, Inc. for the purpose of acquiring air-mail routes from the Postal Department. The mail pickup system would eliminate landings and take-offs and, as well, could serve towns that did not have an airfield. Constantly in need of money through this period, in 1938 Adams and chief pilot Norman Rintoul, flew to Hyde Park, New York in order to fly Eleanor Roosevelt to West Virginia to witness the system in operation the next day. Adams had contacted Eleanor several years before in hopes she may favorably peek the US Postal Department’s interest in his system. By chance, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Jr. and his wife Ethel were at this dinner. Ethel expressed that her cousin was a glider expert and may be interested in the pickup system. Basically this was the introduction of Richard C. duPont to Adam’s airmail pickup system. On 12 May 1939, AAA began operating a mail service under a one-year U.S. Postal Department contract. Two mail routes were granted. Route #1001 was from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh with pickup from the small town in between. Route #1002 started and ended at Pittsburgh connecting small towns southwest of Pittsburgh to West Virginia into southern Ohio as far west as Gallipolis then back to Pittsburgh. The company used a specially equipped single-engine Stinson SR-10C monoplane to pick up US Postal Service mail pouches on the fly at small rural towns having no airport. To satisfy the requirements of the US Postal Service AAA fitted its aircraft with the company’s Model 4 winch with a braking mechanism. A cable ran through guides to an external boom mounted on the fuselage and then to a hook at the end of the boom. The system functioned much like a fishing rod and reel. The pickup airplane would fly low (approximately 20 feet above the ground) over the pickup station and hook a nylon loop stretched between two poles approximately 12 feet above the ground. Just as the hook snagged the loop the pilot would pour on the power and climb away at a fairly steep angle, dragging the mailbag behind the airplane on the cable. At the moment the hook made contact the winch would feed out cable to absorb the inertial energy of the pouch weight. The operator would then retrieve the pouch by rewinding the steel cable. This US Postal Service aerial retrieval system was the forerunner of the USAAF glider retrieval system, which was also developed by AAA. In July and September 1941 the company used the Model 4 pickup winch installed in the company’s Stinson SR-10C to successfully snatch a 500 pound gross weight “Midwest Utility” glider from the ground. Following this demonstration, the company issued a report asserting that they could build a system to pick up heavier gliders. The architects of the US Army Air Force Glider Program decided that the large military troop/cargo gliders were simply too expensive to be abandoned after one combat mission and had recommended that a system be developed to retrieve them. AAA sought to satisfy this need. Since the glider landing zones were inaccessible to tow planes, the only way to retrieve the gliders was by snatching them off the ground with an aircraft on the fly. During further tests in 1942, AAA used the Stinson SR-10C to successfully snatch a two-place Schweizer XTG-3 military training glider. Richard duPont piloted the glider. As a safety feature the company aircraft was equipped with cutting knives mounted in front of the wheels in the event that the tow rope should snag on them. During further demonstrations a Piper Cub, less its propeller, was successfully snatched from the ground. That same year glider snatch pickup demonstrations were conducted at CCAAF with the larger and heavier Waco 9-place XCG-3 troop/cargo glider. A twin-engine Douglas B-23 Dragon bomber equipped with the newly developed AAA Model 40 winch retrieval system was used as the pickup aircraft. Like duPont’s Stinson, the B-23 was equipped with cutting knives mounted forward of the landing gear. Colonel Frederick R. Dent, Jr., head of the Glider Branch at Wright Field, piloted the XCG-3 for its first snatch flight test in December 1942. The system performed as advertised. USAAF contracts to AAA were let in 1942 to provide pickup equipment initially for training gliders, and finally for gliders weighing from 8,000 to 16,000 pounds. A new AAA Model 80 heavy-duty pick up system was subsequently designed incorporating an improved braking system that made use of a “time delay” function where the first several drum rotations had a reduced braking force to allow the drum to accelerate without applying high cable loads, and then the final brake force was gradually applied until the preset line tension was established. Much of the credit for the successful testing of the Model 80 system belongs to the Captain Chester Decker of the Glider Branch at CCAAF, who was responsible for developing its military application and training many glider tow pilots at Laurinburg-Maxton Army Air Base in its use. In addition to Decker, Norman Rintoul and Lloyd Santmyer, who previously had flown mail pickups for AAA, were very instrumental as tug pilots during the testing and development of these systems. Captain Lee Jett at Wright Field and CCAAF flew pickup tug for these test flights as well as dead weight and sheep and human pickup experiments. Jett later was reassigned to First Troop Carrier Command at Stout Field, Indianapolis. He instructed the pickup procedure with his favorite crew chief, Louie Winters and favorite CG-4A pilot, Lt John Bryant. Jett also commanded a War Bond drive, glider/airborne, demonstration team which included Winters and Bryant and others including Jackie Coogan who had recently returned from the Burma area. By the end of 1946 Lee Jett had flown as tug pilot for more than 2,500 snatches. Much like the original US Postal Service pickup system, the AAA M-80X system consisted of the following components:

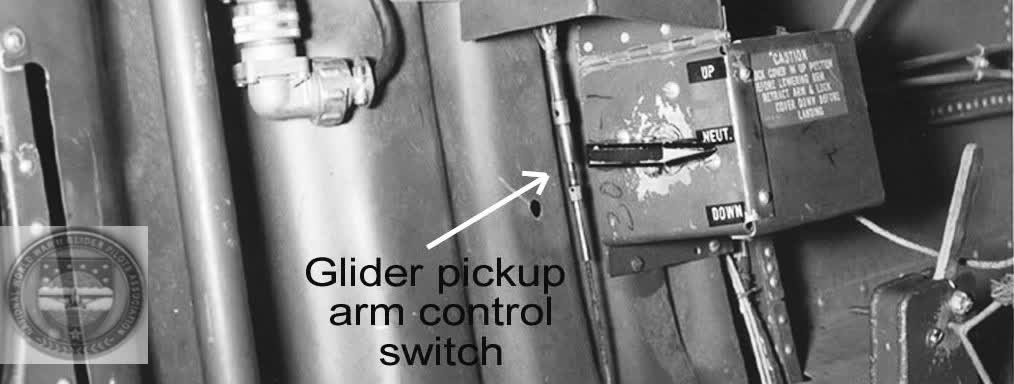

Initial flight testing of the Model 80 system was conducted by AAA in the first half of 1943 at DuPont Airport in Wilmington, Delaware. Subsequent military flight testing was switched to CCAAF. Until fall of 1943 there was only one model 80 unit installed in a C-47. CCAAF ground personnel were taught to set up the 12 foot ground station poles 20 feet apart positioned ahead and slightly to the right of the glider. They then attached the 80 foot closed loop of 15/16th inch diameter nylon line to spring clips on the poles so that the rope was nearly taut. The 80 foot loop was attached through metal linkage to a 225’ foot nylon leader 15/16th inch diameter. A short 18” safety link of 11/16th diameter nylon rope was attached to the leader at the glider. The use of nylon tow ropes made of nylon fiber developed by the E. I. DuPont Company greatly enhanced glider “snatch pickup” operations. This fiber, when woven into a rope, was elastic. It could stretch 25% of its length and thus absorb much of the shock as the glider became airborne. The rope would return to its original length. Because of this characteristic, the average acceleration for pick up was only 7/10th of one G, which according to AAF Manual No. 50-17, lasted about 6½2 seconds. This is significant if you consider that pilots catapulted from an aircraft carrier experience 2½ G’s and some of today’s roller coasters pull more than 3 Gs. The glider usually became airborne within 100 feet and was moving at same air speed as the tug. The twin-engine Douglas C-47 Skytrain was the primary aircraft used to test the Model 80C Pickup System. The mechanism was bolted to the floor on the left side of the cabin about six feet from the front bulkhead of the aircraft. The reel was equipped with a friction brake that could be adjusted for different glider weights. The amount of cable payed out was directly proportional to the weight of the glider and the nature of the acceleration of the glider after pickup. Under most circumstances the cable pay-out was usually less than 600 feet. The maximum designed load of the M-80C pickup unit was 8,000 pounds. In addition to the normal crew of a pilot, copilot, crew chief and radio operator, the retrieval aircraft required a winch operator. The aircraft crew chief and radio operator assisted the winch operator if necessary. The winch operator’s function was to properly set the pickup drum clutch snubbing adjustment, which was based on the glider’s weight and the aircraft’s proposed speed at the instant of the cable hook/glider rope loop engagement. The drum manufacturer (General Aviation) provided a chart with recommended snubbing settings for various glider weights/aircraft contact speeds, etc. The shock of the initial contact with the nylon rope was the critical moment that placed the greatest stress on the flexible steel cable. At the very instant of “snatch” the winch operator’s judgment received its most critical test. A misjudgment could result in a broken cable and possible severe injury to the operator or damage to the aircraft, or both. When retrieving a glider the tow plane approached the ground pickup station at an angle about twenty feet above the terrain at 130 to 145 miles per hour IAS (Indicated Air Speed), depending on the gross weight of the glider. At the moment the tow rope was snagged by the aircraft’s trailing hook the winch drum began to pay out cable rapidly, then more slowly as the brake took effect. Some of the initial shock was absorbed by the unwinding cable and the elasticity of the nylon tow rope. In a matter of about seven3 seconds the glider would accelerate from 0 to 120 miles per hour IAS and would become airborne in as little as sixty (60) feet, depending on the glider load. At the same time the extra weight of the glider slowed the tow plane to about 105 miles per hour. Slowly, the cable drum braked to a full stop and then reversed. The glider, now 500 or more feet behind the tow plane, was slowly winched in to the tow rope hook. 1943 was a year of great achievement for aerial pickup technology, but a sad year for the AA Company because of the untimely death of one its founders, Richard C. duPont, in a glider accident on 11 September 1943 at March Field, California. Mr. duPont was a passenger aboard an experimental Bowlus MC-1 glider being tested when it unexpectedly crashed. Earlier in July, the AAA’s glider retrieval system had been successfully tested at CCAAF with a C-47 retrieving a glider with a fixed landing gear and one equipped only with skids. Surprisingly, it was reported that the engines of the tow plane showed less strain during the pickup than during a conventional takeoff. When the snatch pickup system became operational glider pilot students at the Glider Crew Training Center at Laurinburg-Maxton Army Air Base (LMAAB) were required to participate in one snatch pickup as pilot and one as copilot. Prior to their first snatch pickup glider pilots were given the following classroom instructions:

Once the retrieval of a single glider was perfected experiments began at CCAAF to retrieve two gliders with a single tow plane. In this operation, two gliders were properly lined up with two separate tow ropes and two separate ground stations for holding the pickup loop. The C-47 picked up the first glider and then circled back and snatched the second glider. The difficulty in the double retrieval was the transfer of the first tow rope from the winch pickup cable to the normal tow point on the tail of the tow plane. This was necessary so the winch cable and pickup hook could be reset on the boom in order to pick up the second glider. The C-47 pilot for the first double pick-up experiment was Lt. Lee Jett, with Louie Winters as crew chief, and other enlisted men handling the winch and associated operations. Lt. John Bryant piloted the first glider snatched and Lt. Joseph Mollinary piloted the second glider. On the double pickup the following method was used to remove the first glider pickup loop from the hook and transfer it to the tow release on the tail of the C-47; First, one end of a doubled nylon rope was tied off to a tie down ring installed in the floor of the aircraft. The cable winch then reeled the pickup loop near the door of the aircraft. A gaff hook was used to insert the free end of the doubled rope through the pickup loop and bring the free end of the doubled rope back into the door. The free end of the doubled rope was then hooked to the working end of a double block and tackle. The block and tackle was used to pull the pickup rope loop and pickup hook to the edge of the door of the C-47. The free end of the short doubled was secured to another tie down ring and the block and tackle removed. A pre-attached short tow rope running to the tow socket of the tow plane tail was connected to the loop and the pickup hook removed from the loop. To release the tow rope from the short doubled holding rope and allow the tow rope to go to the tow socket, the doubled rope was chopped through with a fire axe. The pickup hook was reset in the pickup arm and the second glider was picked up and towed on the winch cable. The procedure took less than fifteen minutes. As the requirement for gliders at training bases became more acute during WWII it was not uncommon for CG-4As to be snatched into the air from the manufacturer’s plant by aircraft on the fly rather than being shipped by rail. This was frequently the case at the Ford Motor Company plant at Iron Mountain, Michigan, the Waco Plant in Troy, Ohio, and the Gibson Company Plant in Greenville, Michigan. A double snatch at the Ford plant was not uncommon. Glider snatch pickups were more common in the CBI (China-Burma-India) Theater than in Europe during World War II. The first snatch pickup under combat conditions was conducted by the 1st Air Commando Group (1ACG) in Burma in 1943. That organization received the very first C-47 transports equipped with glider pickup equipment. Glider retrieval was so new at the time that AAA found it necessary to send technicians to India to instruct 1ACG personnel in its use. The 1st Air Commando Group trained eight crews to perform glider pickup duties. Each glider crew consisted of a pilot and a copilot. This special unit, headed by Lt. Samuel “Buck” Altman, flew supplies to British General Wingate’s Chindits fighting the Japanese behind enemy lines and on the return trip evacuated the sick and wounded by snatch pickup. In June 1944, 700 to 800 sick and wounded troops were evacuated from the Kabal Valley in Burma. Altman led the number of pickups with 25, while Flight Officers Harry McKaig, Charles B. Turner, Paul B. Higgins and Solomon Snitzer had 15, 11, 9, and 2 or 3 pickups respectively. In March 1944 alone, Turner flew nine pickup missions. During these very dangerous snatch pickups not a single C-47 or CG-4A glider was lost, and no injuries were reported. On 21 June 1944 in Europe, Captain Roy Sousley and ten other glider pilots from the 437th Troop Carrier Group were sent to Normandy to make preparations to retrieve gliders used in the D-Day invasion. Sousley had orders from 9th Air Force to conduct a survey of the entire American airhead area and then dispatch a report to England on how many gliders could be retrieved by the aerial snatch method. The end result was that only 13 of the 517 D-Day CG-4A gliders were snatched out of the fields and returned to England. Unfortunately, many of the gliders that were repairable and could have been recovered were damaged beyond repair by German shelling, locals and ground troops. Reacting to pressure applied by General Arnold, who was greatly dis- pleased with the Normandy and Southern France glider recovery operations, General Brereton undertook a vigorous effort to retrieve as many gliders as possible from Holland. Between 25 September and 1 October 1944, three repair teams of 150 glider mechanics each was sent to Holland to repair and salvage damaged American gliders that were scattered all over the liberated portions of that country. The weather during that period was terrible. On 17 October a storm blew across Holland, wrecking 115 gliders that had been repaired and readied for aerial snatch pickup. By mid-December, when salvage operations ended, only 281 of the 1900 CG-4As used in Operation Market-Garden had been snatched out of Holland. The following April, 148 of the 906 CG-4As used in the Rhine River Crossing mission in March had been repaired and snatched out of Germany. On 22 March 1945, an historic med-evac glider mission took place in Europe. Two CG-4As landed in a clearing near the Remagen bridgehead in Germany to evacuate twenty-five severely injured American and German casualties. Each glider was fitted with six stretchers suspended by nylon straps on each side of the cargo area. Once loaded the gliders were successfully snatched from their landing site by a C-47 transport and flown to a military hospital in France. An Army nurse from the 816th Medical Evacuation Squadron, Lt. Suella V. Bernard volunteered to accompany and care for the wounded enroute, thereby becoming the only nurse to participate in a glider combat mission during World War II. A second high profile glider retrieval mission was carried out following the crash of a C-47 in Hidden Valley, New Guinea, on 13 May 1945. Two paratrooper medics jumped at the crash site five days later to care for the injured survivors, two soldiers and a WAC corporal while rescue plans were formulated. It was decided that the safest method of rescue was to land a CG-4A glider at a site ten miles below the crash and retrieve it by snatch pickup. On 20 May Captain Cecil E. Walter, Jr. and eight additional paratroopers jumped below the survivor’s campsite to locate and clear a site for the glider to land. It took three trips to extract the survivors and the rescue team from the valley. This remarkable rescue mission is fully described in Colonel Edward T. Imparato’s book, “Rescue from Shangri-La,” 1997 Turner Publishing, Paducah, KY.

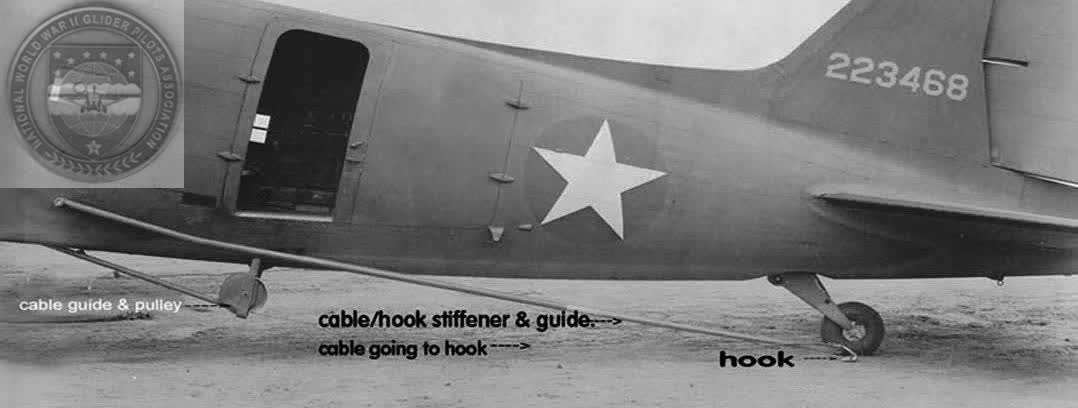

Glider Pulled Into the Air from a Standing StartFor ground tow, the normal CG-4A tow line was nylon, 11/16 inches diameter, 350 feet long. A glider snatch was accomplished by a C-47 tow plane flying just 25 feet or less above ground level with a hook trailing behind on a 3/8” diameter steel cable that payed out from a revolving drum. The hook snagged a 15/16” diameter nylon tow line suspended between two twelve foot tall vertical poles, 20 feet apart, sweeping the glider airborne from a dead standstill to 120 mph in 7 seconds with a “G” force of approximately 7/10th of ONE G. Used effectively in Burma! After unloading equipment loaded up with stretcher and walking wounded and then snatched out. Returned to Hospital in about 2 hours as opposed to two months by ambulance from out of the jungle. POLES AND NIYLON ROPE READY FOR SNATCH National Archives GLIDER READY AND WAITING National Archives GLIDER LINING UP FOR THE SNATCH National Archives C-47 IN THE LOWEST POINT OF THE APPROACH WITH PICKUP ARM READY TO SNAG THE NYLON ROPE SUPPORTED BY THE VERTICAL POLES. National Archives SNATCH IS MADE! National Archives GLIDER MOVES FORWARD National Archives AS GLIDER LEAVES THE GROUND ANOTHER IS BROUGHT IN National Archives |

|

FURTHER READING: by Keith Thoms Glider Retrieval Operation by Hans den Brok |

GLIDER PICKUP/Snatch Snatching a Glider RECLEMATION American Glider Pilots Captured by British A/B by William SIMONSEN Double Snatch by Charles Day First Glider Snatched from Normandy by Gerald BERRY REMAGEN Glider Retrieval by Jungle Moonlight: Burma, 1944 by Leon SPENCER Charles DAY Keith H. THOMS NWWIIGPA Deputy Wing Commander

Eastern United States Military Snatch Pickup Summary

Glider Pilot Check List

Glider Ground Crew Check List

|

CG-4A WWII CARGO GLIDER CG-4A WWII CARGO GLIDER GENERAL SPECIFICATION - CG-4A

Wing Span -- 83', 8" Length (Overall) -- 48', 3-3/4" Height -- 12', 7-7/16" Weight, design -- 3,750 lbs Gross Weight, design -- 7,500 lbs Wing Chord -- 10', 6" More Specifications

CG-4A WAS FLIMSY? COMMUNICATION SYSTEM CG-4A Loads CG-4A Load Facts CG-4A Cockpit CG-4A Instrument Panel  STORIES:

|

The HORSA GLIDER |

OUR TOW SHIPS |