National WWII Glider Pilots AssociationLegacy Organization of veterans National WWII Glider Pilots Association. Discover our History, Preserve our Legacy | ||

Phillip Gerald Cochran

Photo Courtesy of USAF Archives |

Phillip Gerald Cochran was an officer in the USAAF during World War II. Although he was a fighter pilot, he developed many tactical air combat, air transport (both C-47 and gliders) and air assault techniques during the war, particularly in Burma operations as a co-commander of the 1st Air Commando Group with Colonel John R. Alison. This Group was the precursor to modern day Special Operations, now a Major Command in the USAF. |

|

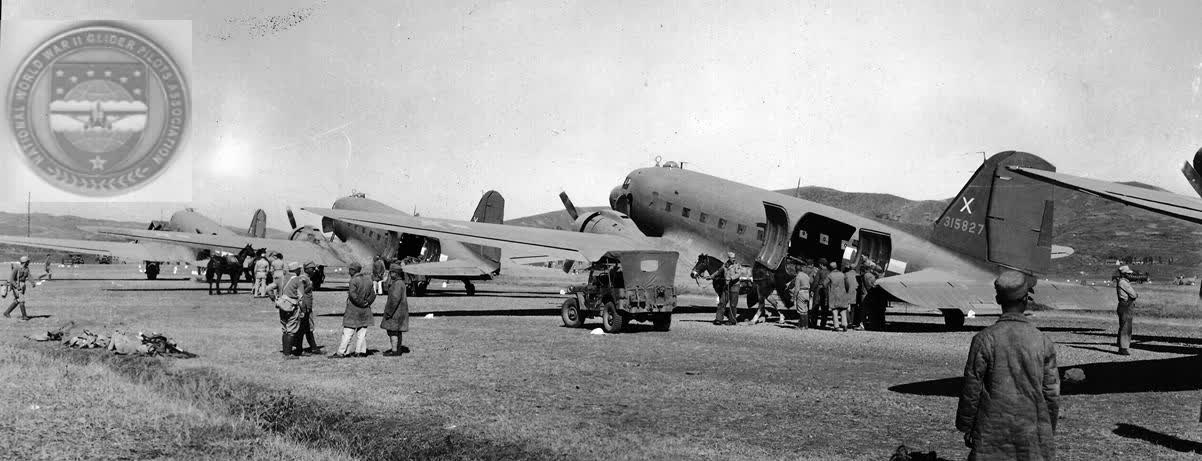

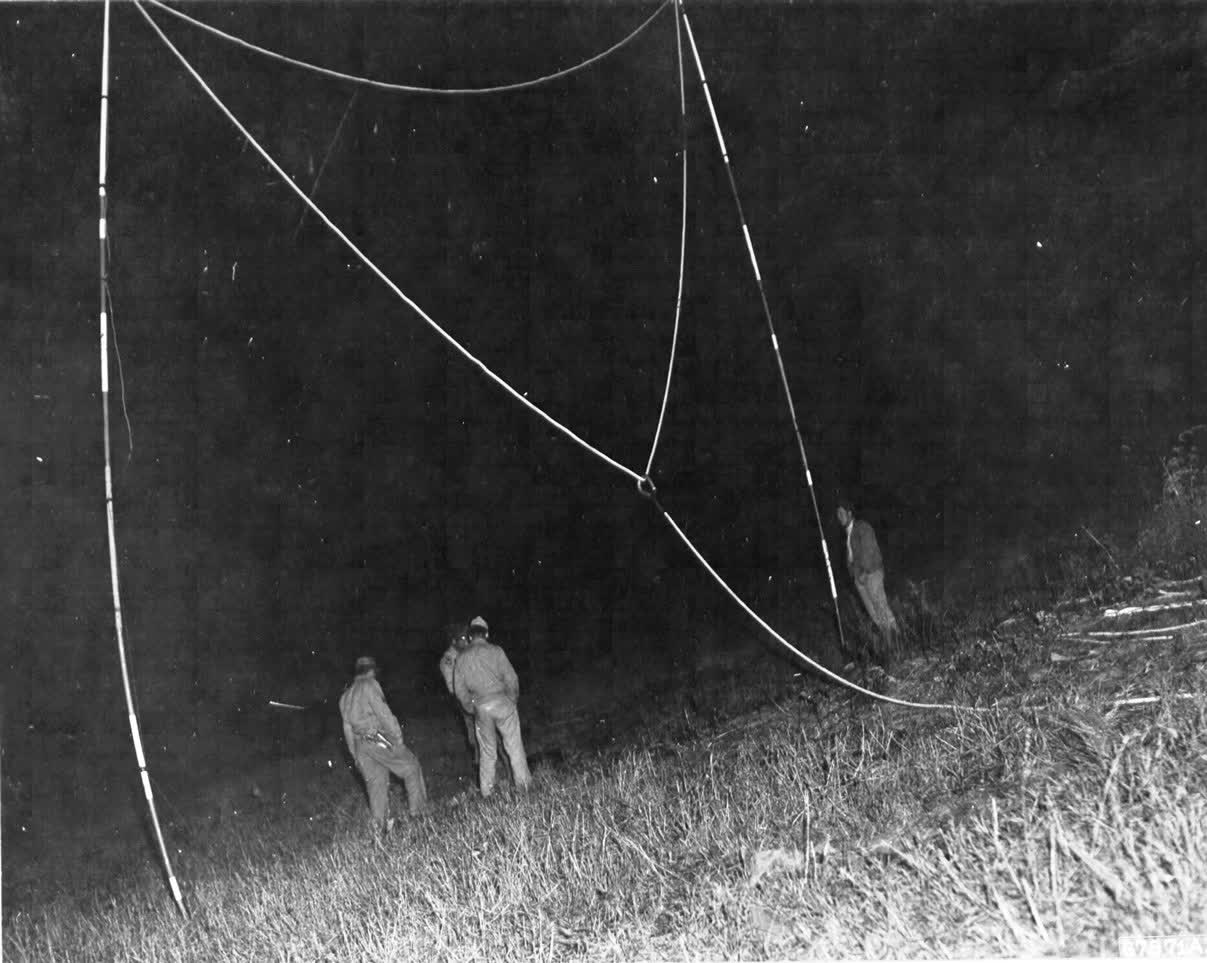

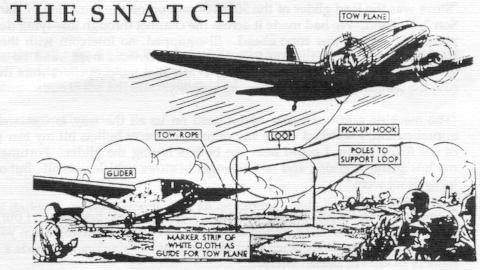

I first came across the name Phillip G. Cochran while researching and writing my next book I hope to publish: Leading the Way to Victory a History of the 60th Troop Carrier Group 1940 – 1945. On the night of November 7 - 8, 1942, thirty-nine C-47s of 60th Troop Carrier Group (60th TCG) carried 550 paratroopers of the 2/509th Parachute Infantry Regiment (2/509th PIR) on the first combat airdrop in U.S. Military History as part of the initial Invasion of North Africa; code name Operation TORCH. Nearly two months later, on the night of December 26, 1942 three C-47s of the 60th TCG were again carrying 30 paratroopers and 1500 pounds of TNT on a secret mission to destroy a railroad bridge 90 miles behind enemy lines in Tunisia. Flying as an extra crew member and guide on the lead C-47 was P-40 fighter pilot Lieutenant Colonel Phillip G. Cochran. Just a few nights prior, Lt. Col. Cochran unsuccessfully tried to bomb the same railroad bridge. Flying 50 to 100 feet above the deck, the three blacked out C-47s flew undetected through German lines to their objective area. While the drop mission was successful and put the paratroopers within a few miles of the bridge, the raiders did not accomplish their mission before being discovered by Arabs and Germans. Many of the raiders were captured, a few killed and a few more escaped back to Allied lines. A colorful individual and natural leader, the exploits of Cochran as a fighter pilot were already well known in North Africa and he was mentioned in press reports. While leading the 58th Fighter Squadron flying out of Thelepte, Cochran dropped and skipped a 500 pound bomb directly into German Headquarters at the Hotel Splendida in Kairouan, Tunisia. Lieutenant Colonel Cochran destroyed enemy telegraph wires by flying over them with a lead weight on the end of his P-40, a tactic he employed later in Burma as well. In May 1943 Cochran returned to the United States with a Silver Star, A Distinguished Flying Cross with two oak leaf clusters and numerous other medals pinned to his chest. He was given the job of training three new P-47 Fighter Groups being formed and was ready to take command of one and head to Europe again. Now a Colonel, three months later both he and his friend fighter pilot John R. Alison were summoned to report to General H. H. "Hap" Arnold, the Chief of Staff of the USAAF to receive news of their next assignments (both were already slated for Fighter Groups heading to Europe). All the two Colonels knew was that they were being considered for something vague that nobody could talk about. Both were thinking what the hell have we done? Before they met with General Arnold, General Hoyt Vandenberg, Arnold's Deputy met with the two and let them in on the little bit he knew about what General Arnold had in mind. Unknown to both of the two Colonels, Arnold had hand-picked the two as candidates to lead a new type of Air Combat Unit known only as Project 9. In fact Project 9 was in such an infancy stage (all in General Arnold's vision) that no table of organization or equipment even existed for the unit! Cochran reported in first and before General Arnold even said a word, the "Sierra Hotel" Fighter Pilot bluntly told the Chief, I don't want any part of it.i Without showing any emotion, Arnold asked him to state the reasons for his position. Cochran replied that he had a lot of combat experience, was already slated to go to England and that Europe was where the action was. He did not want to be sent to some doggone offshoot, side-alley fight over some jungle in Burma that doesn't mean a damn thing. ii At this point General Arnold halted Cochran's rant with I don't know what kind of Air Force office I'm running here when guys come in and tell me they are not going to do something! iii This quieted Cochran down and the meeting continued on. Still trying to get out of the command assignment that Arnold had not fully explained, Cochran mentioned Allison and assured the general he was the right man for the job. Arnold then let the colonel know that he did not need his advice to make a proper decision and told him to get out of here and that he would let him know his future assignment tomorrow. Colonel John R. Alison reported in to General Arnold next with similar complaints and that Colonel Cochran was best slated for the job so he could go on to a fighter group in Europe - the best job in the Air Forces. After calming him down too, Arnold told him to report back tomorrow. The next day two dejected fighter pilots commiserated about their fate as they waited in the outer office of General “Hap” Arnold. Both men were still determined to get out of whatever Arnold was going to offer them. Soon they were called in; with Arnold were Generals Hoyt Vandenberg and Barney M. Giles Chief of the Air Staff. General Arnold opened the meeting by saying, boys I've got big jobs for you. Arnold then went on to educate the two colonels on the organization they would lead. A most unique organization that did not spring from a USAAF need, but rather a British requirement – an air unit to support the Long Range Penetration Groups (LRPGs) of British General Orde C. Wingate. Neither Cochran nor Alison had even heard of Wingate and were not aware of his exploits deep behind Japanese lines. As Arnold explained the concept he began by describing the use of L-5 aircraft (small liaison aircraft) to support ground troops deep in the jungle behind enemy lines. As soon as he heard L-5, Alison blurted out: if you’re going to give me L-5s, you don't need me, I am a fighter pilot. Cochran interjected on his friend's behalf He did not mean that. Arnold leaned back in his chair and continued on saying the L-5 was just a starting point and he envisioned a much-larger group, but that they would need to design it. Arnold explained his vision which included the air group spear-heading the assault, not just supporting it – go over and steal the show he stated. The men were impressed with Arnold's vison and passion and soon were on board with the idea, soon the rest is history. Arnold told the two men to study Wingate, find out what he needs and that anything the two Colonels wanted was priority 1. Even though most histories mentioned the two were co-commanders, right from the start, the two men had an agreement that Cochran was the Commander and Allison his Deputy. The two men thought so much alike essentially they were of one mind. Cochran flew to England to meet with Wingate and asked him what he needed, while Allison stayed behind to obtain men and equipment. Wingate told Cochran of the secret plan to take back Burma and that he needed Cochran to be able to airlift out casualties from small cleared landing strips, air drop supplies and ammunition, provide air transport for heavier equipment and execute close air support missions for his light and mobile forces. Up to this point in the war, Wingate’s LRPGs (Chindits) would ingress into Burma behind enemy lines with donkeys carrying their supplies and ammunition. It would take a month to move his force a couple of hundred miles inland through heavy jungle and by the time the men got to their objective area they were tired and short on supplies. Wingate’s tactics included small raids on Japanese installations and forces and then his force would melt back into the jungle before the Japanese could react. At this point, Cochran said to Wingate, how about if we flew your men, supplies and ammunition to their objective area in gliders in one hour instead of having them walk 30 days to get there? Wingate looked at him incredulously. After speaking with Wingate, Cochran flew back to the States and created his shopping list for General Arnold to build his new air group: Thirteen C-47s, twelve UC-64As, one hundred CG-4As, One hundred L-1s/L-5s, six YR-4Bs and thirty P-47s. Also, he needed all of this equipment delivered to India to form, stage and train his new Air Commando Group. On October 4, 1943 the War Department authorized the manning of the "Provisional Air Commando Force" consisting of 87 officers, 75 flight officers and 361 enlisted men. iv [Note: Cochran received P-51As instead of P-47s and later seventy-five TG-5 training gliders and twelve B-25H medium bombers were added. This diverse group of aircraft in one unit was ahead of its time; think of the capability contained in a modern carrier strike group!] Later, in March 1944, the Group would officially be designated the 1st Air Commando Group (1st ACG). Cochran and Alison worked hard recruiting high-caliber personnel to fill out key staff and section leaders in the group. The C-47 section was commanded by Major William T. Cherry, Jr. with Capt. Jacob P. Sartz his deputy. The C-47 section included Capt. Richard E. Cole who flew as Jimmy Doolittle’s co-pilot during the Tokyo raid. Selected for command of the CG-4A Glider Section was Capt. William H. Taylor, Jr. a soft-spoken Mississippian who had conducted experimental jungle landings with CG-4A gliders in Panama. v The new section commanders were then charged with recruiting high-caliber personnel for their sections. Two days after being selected himself, Glider Section Commander Capt. William H. Taylor traveled to Bowman Field, Louisville, Kentucky to recruit personnel. Over the next couple of days he personally selected 75 glider pilots and 15 glider mechanics. One of the glider pilots Taylor recruited was F/O John L. Coogan aka Jackie Coogan film star and ex-husband of Betty Grable. Stops at Sheppard Field, TX and Maxton Field, NC netted an additional 10 glider mechanics for the section. One week after visiting Bowman Field, Taylor organized the volunteer glider pilots into four flights. Headquarters flight was placed in command of Capt. Vincent Rose, First Flight under Lt. Donald E. Seese, Second Flight under Lt. James Siever, and third Flight under F/O Thomas Martin. vi All of these men were told to report to Seymour Johnson Field, Goldsboro, NC to begin training. Upon arrival in NC, the glider pilots were issued paratroop uniforms and USMC jungle boots. Next all were put through a grueling 6-week long commando course that included hand-to-hand combat, 25-mile marches with full gear and training in all infantry weapons. With limited training time in the States before the group shipped out overseas to India, Taylor focused training on using the automatic tow device, the double tow and flying in the low tow positon. Taylor believed the double tow was the most efficient use of the transport-glider combination; he also preferred to use a low-tow position for the gliders. Taylors reasons for this included that it was much easier for the glider pilot to see the tug by looking up than by looking down, where the tow plane could be obscured by the ground. Also, the flames from the C-47's exhaust stacks helped give a relative position of the glider to the tug, easier to see at night looking up. By early November 1943, the entire 1st ACG was enroute to Karachi, India. The unit’s C-47s were the only group aircraft to fly to India, the rest were either deck loaded on escort carriers or shipped in crates. Upon arriving in India, the glider section was then sent to Barrakpore Field, north of Calcutta to uncrate and assemble their gliders. Captain Taylor attacked this task vigorously. The first test flight of a newly assembled CG-4A took place on December 1, 1943 and by December 18, all 30 of the first shipment of gliders was assembled. Taylor’s men eventually assembled one hundred CG-4As and twenty-five TG-5s. The next phase of training consisted of intensive night glider flying and full loaded landings. The tow planes would approach the landing zone at 200 feet at a speed of 110 mph. When the gliders received a signal light that they were 4,660 feet from the midpoint of a cross marked out with five smudge pots, the glider pilots would release then make a standard approach at 70 mph. Included in this phase was snatching by low flying C-47s in total darkness. This dangerous training was nearly suicidal. The C-47s used the two white lights attached to the top of the two 24-foot tall poles holding the tow cable strung across and a series of red lights on the ground, the three rear red lights (behind the poles) upon the same horizontal plane, and the first red light (in front of the poles) in the same longitudinal plane with the middle red light in the horizontal plane. At General Wingate’s request, a CG-4A glider was rigged to carry three mules on a test flight and landing. To everyone’s surprise the animals walked off the glider without any struggle-Wingate was now a believer in gliders.  Air Commandos practice C-47 glider pickup in India

Poles with tow rope attached being set up for a night "snatch" The American Air Commandos would see their first action in February 1944. American P-51 Mustangs and B-25 Mitchells flew daily missions attacking airfields, railroad yards, river traffic, bridges and storage areas in Burma. British columns had already entered Burma and were pressing the Japanese on the ground. Meanwhile, the transport and glider force continued extensive night training for a major operation that would kick off soon; night snatches were accomplished and night double tows were made. Tragedy struck on the night of February 15, 1944 during one such double tow night training mission. First Lieutenant Kenneth L. Wells was piloting a CG-4A in the low tow position. With him was co-pilot F/O Bishop Parrott and crew chief Cpl. Robert D. Kinney and four Chindits. Something caused Wells glider to slide into the glider of 1st Lt. Donald E. Seese. A loud “crunch” could be heard as the gliders tangled, then Well’s glider fell out of control. All were killed as the glider spun into the ground. Luckily 1st Lt. Seese with help from co-pilot F/O Troy C. Shaw was able to land the glider safely despite losing much of the trailing edge of the right wing.vii

The First Air Commando Force, Commanded by Col. Philip J. Cochran. U.S. Army Air Forces. The Commandoes transported the troops fo Maj. Gen. Orde Charles Wingate’s British command to the field where the ground forces were able to begin operations against the enemy. Troops commanded by Gen Wingate were landed some 200 miles east of Imphal. The glider is on tow 8,000 ft. in the sky over the Chiba Hills, which form a natural barrier between Japanese and Allied territory. Photo Courtesy of National Archives | |

|

The first combat glider mission into Burma was flown on February 28, 1944. Flight Officer John H. Price, Jr. and F/O John E. Gotham piloted a glider carrying a 16-man Chindit patrol. [Note: The author found many instances of gliders being overloaded while writing this article.] The patrol's mission was to conduct a diversionary action near Minsin and to destroy a nearby radio station. |

John Price

Photo Courtesy of son Chris Price |

|

The ground was rougher than it appeared from the air, upon landing the glider hit a trench, the landing gear broke off and a wing was heavily damaged. Pilot Price was slightly injured as were the Chindits. The patrol completed its mission successfully and the two glider pilots with the injured Chindits were instructed to head back to Lalaghat. Soon enough, the ground forces of Wingate and the air forces of Cochran had their chance to prove their concept in combat. Operation THURSDAY began on March 5, 1944, when the first C-47 launched from India towing two overloaded gliders filled with Wingate's troops, equipment, and supplies. In the lead pathfinder short tow glider was Major William A. Taylor; piloting the glider on his left (long tow) was Lieutenant Neal J. Blush. A total of 26 transports towing gliders comprised the first wave. The gliders, carrying from 500 to 700 pounds of excess weight, strained the C-47 tow planes and ropes and caused significant problems. With eight of the first wave of C-47s each losing a glider, Colonel Cochran decided to limit one glider to each remaining transport. This decision allowed the air commandos to successfully deliver Wingate's initial and succeeding forces to the jungle clearings over 200 miles behind Japanese lines in Burma. Additional C-47s from the 27th TCS and 315th TCS also supported this effort. | |

|

|

|

A jeep is loaded into a glider for

Operation THURSDAY

Photo Courtesy of USAF Archives

| A double tow element headed for Burma in

Operation THURSDAY

Photo Courtesy of U.S. National Archives

|

|

During the first day the strip, designated "Broadway," was improved so transport, glider, and liaison aircraft could land safely. They brought supplies, equipment and reinforcements, and evacuated the injured. A second strip, opened by glider assault, relieved congestion at Broadway. Airlift inserted almost 10,000 men, well over 1,000 mules, and approximately 250 tons of supplies. Casualties from the high-risk, untested concept, including missing, were less than 150, and for the first time in military history aircraft evacuated all killed, wounded, and sick from behind enemy lines. The air commandos also protected the British ground forces by harassing the Japanese. This harassment, conducted by P-51s and B-25s equipped with a 75mm cannon in the nose and 12 .50 caliber machine guns, included bombing bridges, strafing and bombing parked aircraft, air-to-air combat, and destroying the communications, transportation, and military infrastructure. Although Cochran's and Allison's men were air commandos from the beginning, the 1st ACG was officially constituted on March 25 and activated on March 29, 1944. The 1st ACG continued to support British forces in Burma through April in an impressive manner. Air commando gliders continued to play an important role in supporting British forces with supplies and equipment for building additional airstrips in Japanese-held Burma. Although glider losses had been high in the initial stages of Operation THURSDAY with landings in rough and unimproved clearings, casualties had been surprisingly light. Without gliders the invasion could not have succeeded. In contrast, the C-47s had a remarkable accident-free record. They flew almost 95% of their missions at night on instruments over hazardous terrain, utilizing short, rough landing strips deep behind enemy lines. Yet these pilots sustained no casualties and lost only one C-47. It struck a water buffalo during a night landing. The air commandos of World War II pushed American airpower into a new dimension and established a number of firsts in our military history. The 1st Air Commando Group inactivated after World War II, on November 3, 1945, and was disestablished by the Air Force on October 8, 1948. viii However, these groups laid the foundation and paved the way future USAF Special Operations.

American Glider pilots huddle on the LZ in Burma -------------------------------------------------

| |

BURMA

Awards THURSDAY

Awards CHOWRINGHEE

Special Briefing Edition:

80th Commemeration 2024

Operation Thursday

Burma Compalation of Info.

The Beginning of Special Operations

Birth of the Air Commandos

Flight Officer Shimulunas

First Published in Briefing 2020

Locating FO Robert Charles Hall

First Published in Briefing 2021

Flight Officer John (Jackie) L. Coogan

First Published in Briefing 2022

Mules in Gliders

First published in Substack

Glider Retrieval:

Glider Retrieval by Jungle Moonlight

Randal Baily interviews Glider Pilot Tim Baily about Liberating Prisoners of Pergu, Burma “Jungle Rescue” glider snatch.

Used effectively in Burma! After unloading equipment loaded up with stretcher and walking wounded and then snatched out. Returned to Hospital in about 2 hours as opposed to two months by ambulance.

Setting out the tow ropes to hook up the gliders.