National WWII Glider Pilots AssociationLegacy Organization of veterans National WWII Glider Pilots Association. Discover our History, Preserve our Legacy | ||

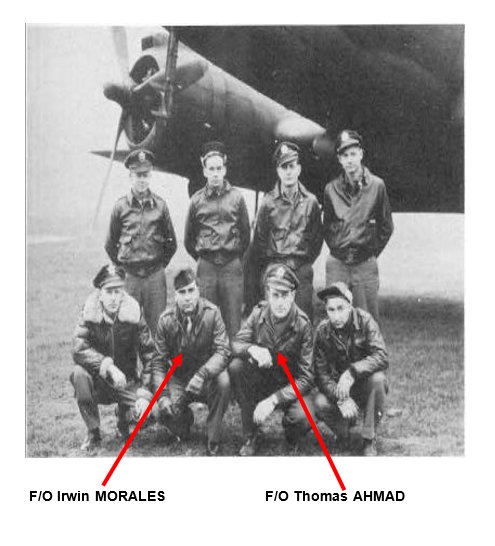

The American Glider Pilot of WW-II, (all volunteers), were the only rated pilots in the long history of the Army Air Force, who, after landing behind enemy lines, donned their steel helmets, picked up their weapon of choice, became infantry soldiers and fought with the airborne troops. They earned the title: Double Duty Sky Soldiers. Flight Officer Erwin Morales was one of these men, with a harrowing tale to tell of his D-Day mission. Morales, a native born American Indian was a Glider Pilot with the 74th Troop Carrier Squadron of the 434th Troop Carrier Group, stationed at Aldermaston, England, in June 1944. The 434th, one of the first troop carrier units to arrive in the E. T. O [European Theater of Operation], had been picked to tow the first serial of 52 gliders into Normandy on D-Day. It was to be a 4:00 AM landing in total darkness, five miles inland, two hours before the beach invasion started. The gliders would be carrying men and equipment of the 101st Airborne Division. Morales and his copilot Lt. Thomas Ahmad were flying glider #42 at the tail end of the formation. | |

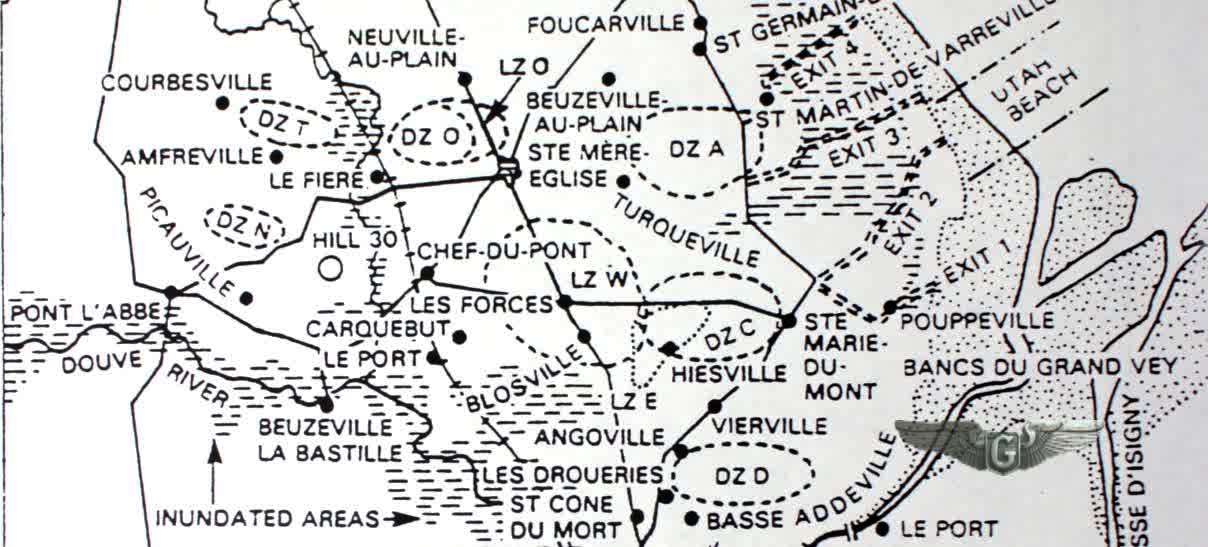

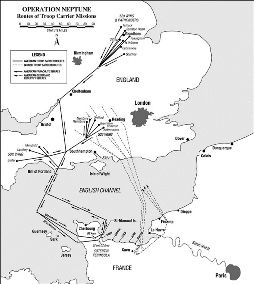

| OPERATION NEPTUNE |

|

The takeoff and flight or the channel was uneventful, but all hell broke loose after we crossed the coast of France. First off, the formation flew into low lying clouds and fog which caused the group to break up with no hope of getting back together because we were only minutes away from our landing zones. Small arms fire and medium flak started coming up from all directions, and made you think of a fourth of July celebration. The C-47 towing glider #51 off to my right (I was flying #49) was shot down in flames and crashed in a swamp five miles for the LZ at Heisville. The pilot was killed by the Germans as he exited the wreck, and the copilot, crew chief and radio operator were captured. Later in the day while they were being transported to St. Lo, the copilot was killed by one of our own planes in a strafing attack on the German convoy. Glider (#51) landed safely and the pilots and airborne men on board linked up with friendly airborne forces.

Morales and Ahmad after release from the tow plane, landed their glider I a flooded area five miles south of Carentan, and twelve miles south of their LZ. This put them deep behind enemy lines in a ver precarious position. At dawn they made their way to the small town of Montmartin en Graingnes. Later in the day, approximately 150 paratroopers and glider men from the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions straggled in. They had also missed their drop zone. They were too far behind enemy lines to break through to allied forces near the coast so they formed a perimeter around the town and dug in to wait for the enemy attacks they knew would come, or hopefully, the beach assault forces would get through to them first. Either way they prepared to fight. The townspeople assisted them in every way by gathering up the arms and ammunition, and supplies that had landed in the fields outside of town. Morales, with other paratroopers, went out each day on patrols to try and find out where enemy positions were located. In the course of these patrols, they blew bridges, cut communication lines and committed other acts of sabotage to hinder the enemy. On the 10th of June they ambushed a German motorized patrol killing four of them. Unfortunately, this alerted the Germans to the fact that a fairly large group of airborne were in their rear. Shortly after this, a large enemy infantry force retreating from the beach head sectors, backed up by artillery, mortars and automatic weapons surrounded the small town. Day and night they shelled the airborne men and made frontal attacks with infantry. All were beaten off, with heavy losses. For five days the small band of airborne men and the two glider pilots, Morales and Ahmad, fought off the Germans, inflicting heavy casualties. The troopers, realizing that their position was hopeless, left their wounded in the town church in the care of two priests, medic civilian nurses. Morales, and others, one by one, and in pars, slipped away through German lines to try and get back to the coast and friendly forces. Ahmad was last seen with twenty five of the airborne men left behind guarding the left flak of the position near the church. They were captured along with the wounded in the church. Morales, after ten days, hiding during the day from the enemy and moving at night, managed to find a small boat, and floated down a small stream to the coast and linked up with Allied Forces. Shortly after this he returned to hour base at Aldermaston. We had all given him up for dead. When the war ended in May of 1945 Morales borrowed a jeep from the motor pool and dove back to the of Grainges to try and find out what had happened to Ahmad, his copilot. The townspeople told him that after the battle had ended, they counted bodies of close to 500 Germans the airborne men had killed. The Germans, enraged over the losses, retaliated by taking the wounded men from the church with the others they had captured, marched them to a field outside of town and shot them. Returning to town, they burnt down most of the houses, shot the two priests, the nurses, and over thirty of the townspeople that had helped the airborne men. Later before returning to base, Morales located Ahmad’s grave in a temporary military cemetery between St. Lo and Carentan. Morales, as an individual, was decorated with the French Croix de Guerre Medal, with Palm, by the French government, and the Air Medal from the USAAF for this mission. The 434th Group as a unit was awarded the Croix de Guerre with Palm for leading the first glider serial on D-Day, ad in August, a second Croix de Guerre with Palm for resupply missions in support of the breakthrough at St. Lo. This was followed up with an award of the French Fouagerre Cord to all members of the 434th Group. | |

|

Mission Chicago 6 June 1944 SERIAL 27 |

Mission Detroit 6 June 1944 SERIAL 28 |

Mission Hackensack 7 June 1944 |

11 Serials - 514 gliders

et Patrick Elie

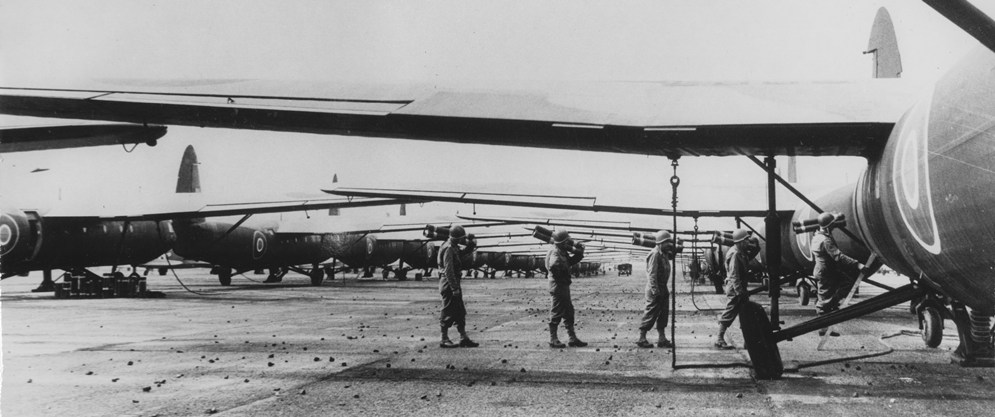

Preparing for the Elmira Mission, Greenham Common.

Neptune Operation air assault route from England.

A C-47 and Horsa combination takes off from Greenham Common as part of the Elmira mission. The C-47 pictured here would later crash on a glider mission to Holland.

Tow planes and gliders of the 439th Troop Carrier Group are lines up on the runway before the Hackensack mission.

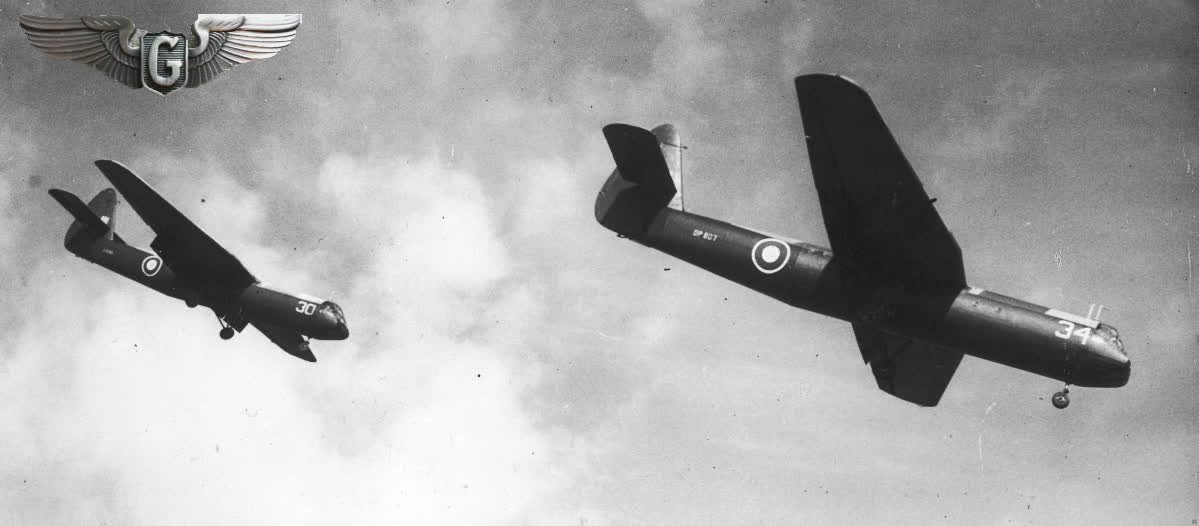

Two gliders of the very first mission in the Normandy fields.