| My nine days of combat: What was to be a landing for glider pilots and a quick exit to fly resupply missions turned out to be a 9 day battle with glider pilots on the front lines facing Germany for 3 of those days. |

History tells us that the mission was not successful and that the British 2nd Army did not get to Arnhem fast enough. The airborne troops there, mainly Polish and British airborne troops could not hold the bridge. The British 2nd Army were slow, took too much time for whatever reason, I personally saw them stop in my area for tea time. The US 101st Airborne units were responsible for the Eindhoven bridge. The US 82nd Airborne was responsible for the Nijmegen bridge. H. Rex Shama, a fellow glider pilot from my squadron, wrote a book titled “Pulse and Repulse” which covered all airborne operations of WWII. He recently died. But before that I was fortunate to have talked to him in Florida and he sent me not only a signed copy of his book but the last copy of his written account of our squadron's activities during the war.

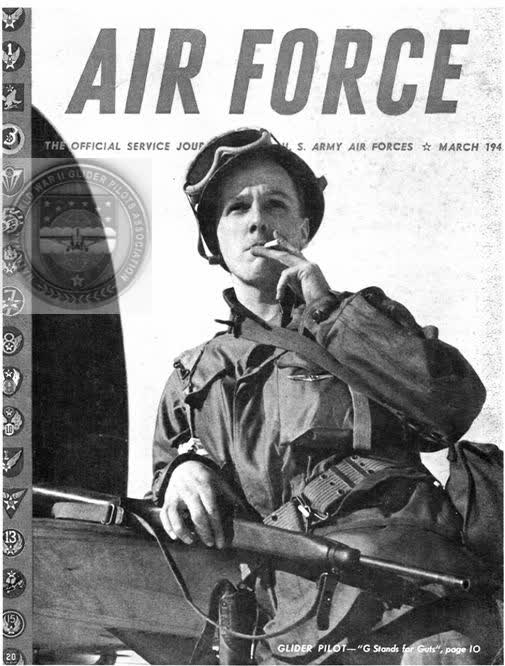

49th Squadron Glider Pilots |  Fred Lunde |

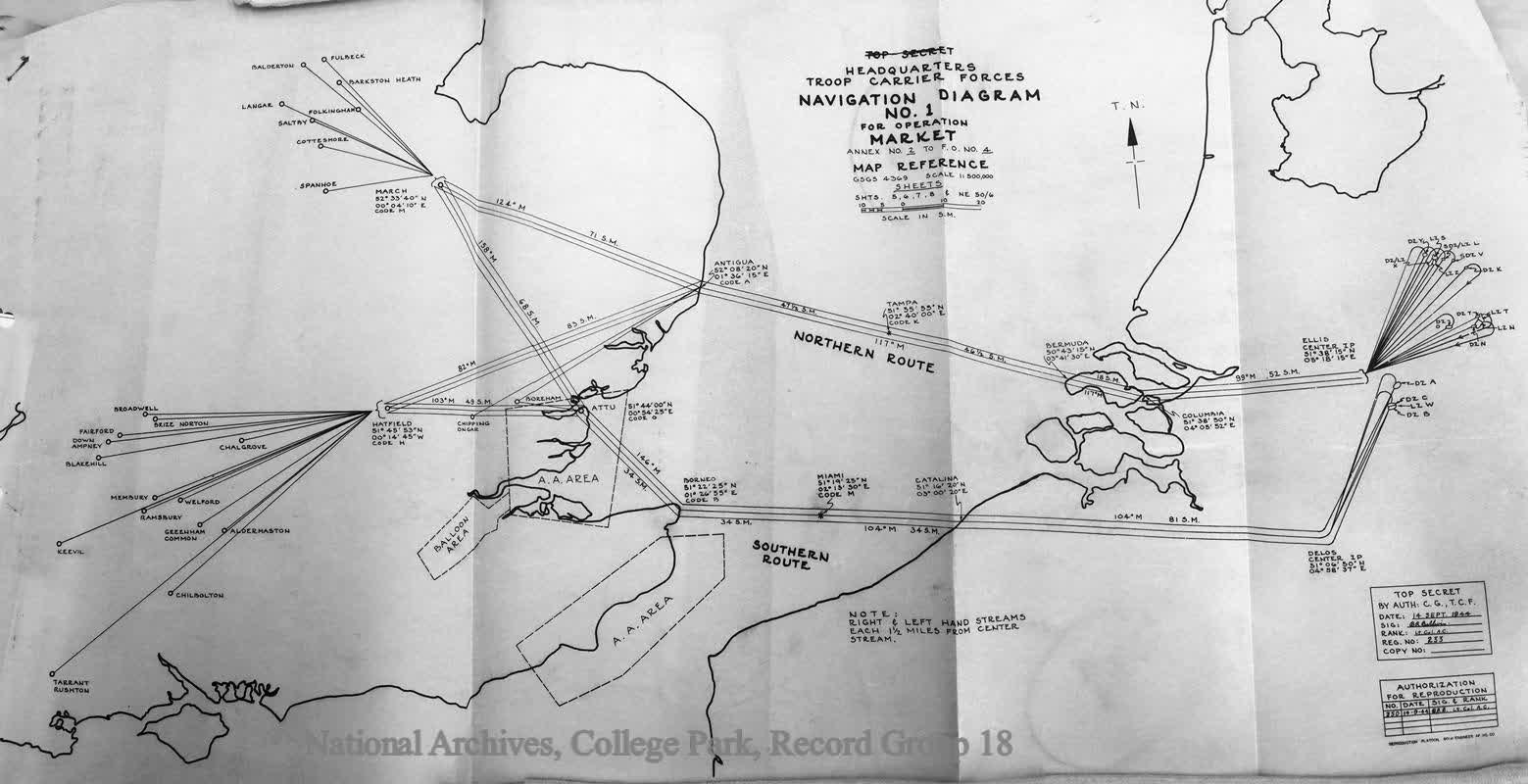

On Sunday, 17 September before noon, heading across the English Channel were 480 planes in eleven serials carrying 7250 paratroopers and glider troops of the 82nd over the northern route to Holland, heading toward Nijmegen. They were met by heavy antiaircraft fire. Ten planes were shot down, two from our squadron of twenty-one which was in the lead serial. Each person has a story to be told.

HOLLAND MISSION DAY 1

Monday, September 18, 1944. So, what was Fred's day like. Early to rise, checking clothing and equipment riding a truck to the landing field, lighting a cigar to reek confidence to my airborne passengers. I’m not sure they saw my fingers shake as I took the cigar from my mouth (confidence squashed). My glider was to carry a trailer loaded with mines, other weapons and airborne troops from the Army Engineers Corps. The glider ahead of mine would have the Jeep that would pull the trailer. Therefor, it was important that both gliders land along side each other. That would be easier said then done.

I checked the glider for possible defects and drew the words MISSIFFY below my window. This was for luck, a reference of my girl, Ida Frances. Since we did not have a co-pilot, I asked the corporal to sit in the co-pilot seat and proceeded to give him a few hints of flying that might help in case something happened to me. I think this scared him more than the good it did. I remember telling the crew, “don't worry I'll get you in and on the ground safely and then you can help take care of me”.

You won't believe the weapons I was carrying, one shoulder burp gun that would fire clips of 30 45 caliber bullets with a pouch over my shoulder with 7 clips, a pouch over the other shoulder that held a lot of hand-grenades (not sure of the number), a 45 pistol with an unknown number of clips and a bayonet in a case strapped to my boot. Equipment that I carried included K rations, cigars, first-aid supplies, a canteen and mess kit and a most important tool---the fox hole digger.

What a sight watching the planes and gliders take off ahead and then it was our turn. The glider is airborne first and stays above the prop wash at all times. The wheels of the glider was dropped so that landing will be on the skids. Just as I was airborne the window on my side pulled apart partially which would have been enough to abort the mission. No way, I waiting too long for this one. I couldn’t trim the controls enough to make it easy to fly. So, for the whole hour of the flight I was fighting to keep the glider in a correct path behind the tow ship. As we approached Holland we could see the flak, clouds of black and white smoke everywhere. The planes flew at a height of about 1000 feet and at a speed of about 90 mph. We could see the planes as they were hit. We would maneuver the glider sideways in an attempt to miss the flak. Finally we arrived at the cut-off spot and down we went. It was important to fly into the wind as you land. The glider with the jeep that I was to follow was landing with the wind. I decided on a landing spot into the wind in a clearing by the farm house. Good decision for several reasons. The field was sandy and easy to land on it. The glider with the jeep wasn't able to stop and went into the woods. Another glider that landed with the wind turned tail over nose trapping everyone in it.

The Germans were firing their 88 millimeter canons onto the field as the gliders were landing. One hit nearby causing our very quick exit from the glider. Earlier I mentioned the window that separated as my glider was airborne. This was my quick exit with a drop down to the grown less risky than being inside that glider. I left my field jacket. Now I crawled as low as I could towards the farm house passing Lt John Van Sicklen sitting under a large tree. He saw that I was without my jacket and said to me, ”Fred, you’ll get cold, better go back and get your jacket”. I stayed on all fours heading to the back of the farm house and into the vegetable patch. There I proceeded to accomplish what I hadn't been able to do for too long of time. I urinated while on my side. The corporal and his men were with me. They were doing much the same.

The firing of the 88's were constant and I suggested to my crew that we head for the prearranged spot for further instructions. We were close. I remember crawling to the woods and then walking normally towards the steeple of a church. Lt John Van Sicklen was killed as he was sitting under the tree mainly from concussion rather than a direct hit. As we congregated and assembled the army engineers left for their groups while the glider pilots were gathered to work with the friendly farmers and their families to gather the supplies, weapons, ammunitions hospital supplies and equipment and whatever else was being dropped by parachute from low flying B24's.

I was treated to tomatoes, cheese and bread as we worked with wagons drawn by horses to bring these supplies to the troops or piled them on the road for anyone in need. That night several of us slept on the hay in the barn.

HOLLAND MISSION DAY 2

We were awaken by the farmer with fresh warm milk to drink. Then we spent most of the second day bringing the supplies to the roadside. Late that afternoon, by the roadside where we had piled a large supply of ammunition, German aircraft must have spotted the sight and began to strafe the area. Across the road from the ammunition supplies was an apple orchard. I remember getting as far into the orchard as I could get to keep trees between me and the strafing aircraft. I fully expected the ammunition would explode. However as luck would have it our aircraft chased the German aircraft away.

Later, about 65 captured Germans were being marched down the road. We, three glider pilots, were asked if we would take these prisoners to a camp established for prisoners of war. This would free up the airborne for other duties. We said, “yes” and took them on the 3 mile march to the camp. Following the prisoners were their family and friends. A jeep drove at us, stopped and told us that the road had been cut-off by some Germans. They suggested that we get the prisoners into an open field and wait for further developments. Our troops were fighting to reopen the road. In the meantime, it was getting dark and I don't mind saying that darkness was scary to me under these circumstances. There was one German that talked perfect english. He had been talking to us. He said that German beer was better than the American beer he got when he visited New York. As it got dark I told this man that he should relay a message to the others that if anyone started any false movements I would throw a grenade into the center of the group. We also tried to send away their families and friends.

We finally received word that the road was again open. We marched them to the stockade and counted exactly the number we started with. I don’t remember how I picked up a long black warm coat. But, alongside the stockade was a greenhouse with all the glass broken so I spent my second night sleeping on a bed of soil in the seclusion of the greenhouse.

HOLLAND MISSION DAY 3

In the morning of the third day, I found myself alone. The other two glider pilots must have gone back after the prisoners were safely in the stockade. As I was walking along the road to return, a jeep came by and stopped. I asked if I could hitch a ride. The answer was "yes" if I helped them place the dead American bodies into a long large grave that was dug for this purpose. I couldn't believe what I was witnessing. Dog tags were kept with the bodies and bags of lime were poured on them. I was told that later they were to be given individual graves.

HOLLAND MISSION DAYS 4, 5 AND 6 - General Gavin puts the Glider Pilots on the line with the 82nd Airborne!

Returning back I was included with a group of glider pilots that were assembled for the purpose of support for the 82nd Airborne. We moved to the front lines facing Germany. We were paired and spaced within hearing distance of each other and told to start digging our foxhole. Little did we know that we would stay in these foxholes for three nights and two days. I was paired with Fred Stafford, a minister's son. At least one of us would stay awake and be alert to anything that might develop such as being overrun by tanks or whatever else the Germans might toss at us. They knew we were there because the fire power that was sent our way was too close for comfort. I remember that, at first, we couldn't tell whether the firepower was coming or going. We hit the foxholes to be sure. We continued to dig deeper so that we could both be comfortable. My buddy, Fred, when taking a jump for the foxhole cut his hand on a K-ration open tin can. He received a purple heart.

Because of the heavy low clouds over the entire area, reinforcements were not able to get in for two more days. Each night we could see nothing ahead of us due to a very thick and dense fog. It could be the reason the Germans did not attack. I remember one gun the Germans used to shoot “Screaming Meamies” which was a psychological weapon to instill fear and was not very accurate. They would shoot one and then move the gun before they would use it again. If they shot it twice in one place we would be able to zero in on it and destroy it.

On Friday night, September 22nd, from midnight until 0900 our sector received a continuous shelling by heavy mortar and 88mm fire which gave us the impression that a large attack would follow. It never came.

HOLLAND MISSION DAY 7 AND 8

With the arrival of reinforcements on 24 September, the 325th Infantry relieved us of our front line duties. We headed down "Hell's Highway" from Nijmegen in a truck convoy thinking that the battle was over for us. Wrong, the convoy stopped and with no traffic coming the other way, we knew something was brewing. A German counter-offensive was taking place. Ahead I saw a convoy of British trucks being picked off one by one by accurate fire power. As they were burning, our glider officers and glider pilots were directing and driving the trucks for a turn around and a hasty retreat. There were a lot of heroes that day.

My glider officer, Lt Max Becker was injured by shrapnel, wounded on the the left side of his face. He fell in the ditch beside the road where I opened my first aid kit that we all carried, literally threw the sulfur powder on his wound and wrapped the large bandage around it binding it in place. Max was conscious at all times. I got the first truck that was turned around. The driver was a glider pilot. I got Max into the truck and slid in myself. As we drove off I'll never forget two things, one the glider pilot had never drove a truck before, asking how do I change gears with my answer at the time was forget it until we get out of the line of fire, stay in the gear you're in and speed it up. The second one was that the actual driver of the truck came running, stood on the running board and said, “I can drive now, boss”, Then there were four of us in the front seat until we came to the first aid station on the highway. I had the driver stop and we let Max off for further treatment. We then proceeded into Veghel where I spent the night in a church dayroom sleeping on a ping pong table.

HOLLAND MISSION DAY 9

Monday, 25th September, after the 101st Airborne fought the battle to reopen the road, we headed back to Brussels where I hitched a ride back to Folkingham, England. As we passed the spot where we had to turn around the battle scene was evident. Bloated cows were lying with feet sticking straight up. Incidentally, Lt Becker returned to the squadron in mid-October and resumed command of his glider troops.

Each glider pilot in this mission received the “Air Medal” for heroic action. In addition, the action of some of us during the skirmish in which Lt Becker was wounded received the “Silver Star” for heroism over and above the call of duty. Since Lt Becker was the one to recommend the award; he asked me if I wanted the medal or would I rather be promoted to commissioned officer status as a 2nd Lt. Of course, my answer was to be a 2nd Lt.

Fred received the Bickett-Ellington award in 2006: