Most WW II Airborne veterans and Troop Carrier veterans have long ago hashed over the Normandy D-Day flights but not all. There is still some lively discussion.

There are a few left who haven’t satisfied themselves enough that portions of a letter that Col. Joe Harkiewicz wrote to his squadron mates in 2001 are included here. Col.

Harkiewicz served as the historian for the 29th Troop Carrier Squadron for many years before he passed away. He was an avid historian, and was extremely impatient with the

unprofessional behavior of today’s Commercial ‘Pop’historians."

At any rate, here are some passing thoughts from his notes:

“It is prudent to remind everyone that IX Troop Carrier Command had no voice in selecting the invasion date, or any choice in the kind of weather we were ordered to fly in.

We assembled and took off as ordered, and flew the mission as best we could under the conditions we faced. And most surprising of all, there was no contingency plan from

SHAEF for coping with the marginal weather.”

Speed for Real

“There are also reports in the ‘pop histories’ about the speed of some of the aircraft during the drops. These reports claim witness to odd altitudes and

excessive speeds over the drop zones. In the ways of war, some of this may have happened, but from USAAF archives, and from readily available airborne records, it appears far from the norm.

“Most Troop Carrier veterans who read the ‘pop histories,’ or who watch the ‘pop TV’ reports, are skeptical of these claims simply because there is no viable way for

anyone in the back of a dark C-47 to read its altitude and airspeed. Not even experienced crew chiefs and radio operators could do that. It is even more difficult from the ground.”

The Illusion of Speed

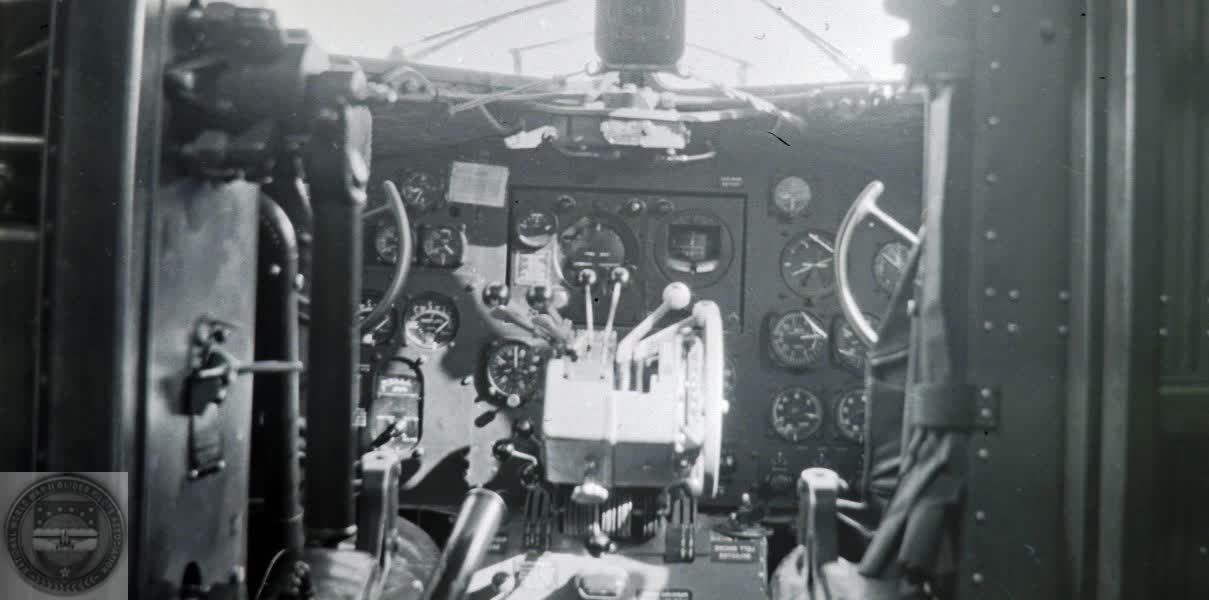

“This is tricky, not easy but here is why some paratroopers may have thought their C-47 gained speed as it approached the drop zone. There are two main power settings for a

C-47, the manifold pressure (a measure of the power that propels the airplane through the air) and the revolutions per minute of the engines. Adjusting these together was a technique

used during every landing to slow the airplane down before touchdown. When some C-47 pilots wanted to reduce power and slow down to lose altitude quickly during a paradrop, they reduced

the manifold pressure (the driving power), and then increased the revolutions to about 2300. The windmilling effect of this faster rpm acted as an air brake. Most of us have had a plastic

toy windmill blade on a stick that we waved around or held out of a car window to make it turn. The principle is the same. The airflow required to keep the plastic blade turning without

applying driving power to it acted as a brake, while the toy turned faster and whizzed louder.

“So it was with the engines. Our formations were briefed to fly over the coast at 1,500 ft. to stay above small arms fire and then to descended to 700 ft. for the paradrop.

The pilots reduced the manifold pressure and started to slow down although the sound of the advancing revolutions could have been misleading. This sounded like more power, but it was

just more noise that led some paratroopers to think the speed was increasing when actually it was decreasing.

“Also, upon reaching drop altitude, an increase in power (throttle) was usually applied to hold and maintain drop altitude and speed. This had to be done very carefully to

keep the airplanes slow and level, without flaps, and without raising the nose. At slower speeds (drop speed) it's much harder to control a C-47. It can be a fight to just hold it

straight and level while being buffeted by prop Wash. This could have caused some paratroopers to believe the pilots were increasing their airspeed.”

The Plus Side

“For almost every ‘pop history’ story that might benefit from further checking, Troop Carrier aircrews can document incidents where pilots made multiple passes at the

DZs, or held burning aircraft straight and level while the troopers jumped. Several of these reports of dedication and heroism that troop carriers remember with pride, are fully

supported in this publication.”

The “200-mph C-47”

“In a recent (2001) History Channel report, it was claimed that a unit of the 101st Airborne Division was flown across the drop zone in a C-47 at 200 mph. This bears checking into;

most C-47s just won’t go that fast in level flight. This might have happened if the pilots were incapacitated (dead/wounded) and no longer in control, and the aircraft was in a power dive.

There could have been such cases.”

Scattering

“The Troop Carrier delivery formation of nine aircraft, V of V’s like a flock of geese, was designed to put the aircraft in the closest proximity to each other and still

avoid turbulence from the preceding aircraft. This is called a serial, and the only way to drop paratroopers close together is for the aircraft to fly close together and release

them at nearly the same time. On D-Day when the aircraft suddenly found themselves in the clouds, the integrity of much of the formation was lost. This, not bad navigation,

is the reason for some paratroopers being scattered around the Cherbourg Peninsula. It was not lack of training in night formation, or in combat experience. And the many stories of flight

crews making return passes over their DZs to drop their troops must be weighed against any conjecture of cowardice among the flight crews.

“Trying to orient oneself after coming out of the clouds was all but impossible. Pilotage (navigating by visual means) depends upon following landmarks, one connecting to the other.

Ground vision was lost while in the clouds, thus disrupting this continuity. The darkness of night, the blackout conditions on the ground, the loss of night vision (compromised by

explosions from enemy fire), and the lack of functioning radio-radar aids, made things even harder.

“Purely and simply, once the formation went into the clouds, some pilots lost their way. Re-establishing themselves accurately was next to impossible, and the scattering of paratroopers

was inevitable. Even today, with the most modern equipment, military paratroopers still need visual flying conditions if they are to drop their troops together.”

Jostling

“Much has been said over the years by the observers and ‘pop historians’ about dodging flak and small arms fire and this needs to be addressed.”

“Once you see the explosion of an anti-aircraft shell (flak), it has done its potential damage, and there is no further use in trying to avoid it.”

“If there was any dodging, it most likely occurred when trying to get out of a lock-on by German searchlights. The odds for survival in this situation were very low.”

“Jostling the paratroopers could have been caused by nearby flak explosions, turbulence from prop wash caused by the disrupted formations, and/or abrupt maneuvering control to avoid other aircraft.”

“Panic was possible, but there has been very little of this documented either among the aircrew or among the paratroopers. That is what one would expect of Americans.”

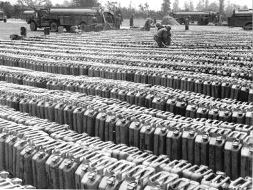

National Archives/NWWIIGPA collection

National Archives/NWWIIGPA collection National Archives/NWWIIGPA collection

National Archives/NWWIIGPA collection